Tesla’s ‘Full Self-Driving’ Beta Software Used on Public Roads Lacks Safeguards

Consumer Reports' car safety experts worry that Tesla continues to use vehicle owners as beta testers for its new features, putting others on the road at risk

After Tesla released the latest prototype version of its driving assistance software last week, reports from owners have gained the attention of researchers and safety experts—both at CR and elsewhere—who have expressed concerns about the system’s performance and safety.

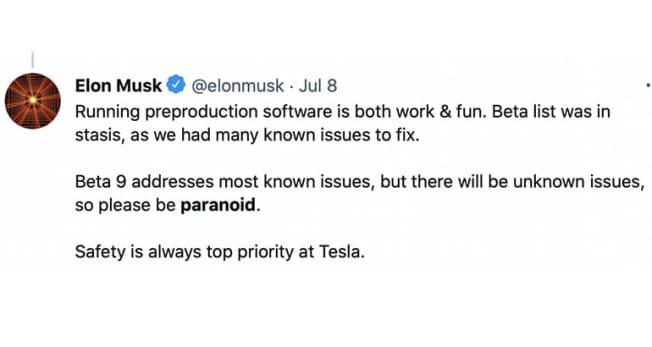

CR plans to independently test the software update, popularly known as FSD beta 9, as soon as our Model Y SUV receives the necessary software update from Tesla. So far, our experts have watched videos posted on social media of other drivers trying it out and are concerned with what they’re seeing—including vehicles missing turns, scraping against bushes, and heading toward parked cars. Even Tesla CEO Elon Musk urged that drivers use caution when using FSD beta 9, writing on Twitter that “there will be unknown issues, so please be paranoid.”

FSD beta 9 is a prototype of what the automaker calls its "Full Self-Driving” feature, which, despite its name, does not yet make a Tesla fully self-driving. Although Tesla has been sending out software updates to its vehicles for years—adding new features with every release—the beta 9 upgrade has offered some of the most sweeping changes to how the vehicle operates. The software update now automates more driving tasks. For example, Tesla vehicles equipped with the software can now navigate intersections and city streets under the driver’s supervision.

“Videos of FSD beta 9 in action don’t show a system that makes driving safer or even less stressful,” says Jake Fisher, senior director of CR’s Auto Test Center. “Consumers are simply paying to be test engineers for developing technology without adequate safety protection.”

As with previous updates, CR is concerned that Tesla is still using its existing owners and their vehicles to beta-test the new features on public roads. This worries some road safety experts because other drivers, as well as cyclists and pedestrians, are unaware that they’re part of an ongoing experiment that they did not consent to.

Source: Twitter Source: Twitter

‘Like a Drunk Driver’

In addition to CR’s engineers, industry experts who have watched videos of the new Full Self-Driving software in action expressed concern about its performance.

Selika Josiah Talbott, a professor at the American University School of Public Affairs in Washington, D.C., who studies autonomous vehicles, said that the FSD beta 9-equipped Teslas in videos she has seen act “almost like a drunk driver,” struggling to stay between lane lines. “It’s meandering to the left; it’s meandering to the right,” she says. “While its right-hand turns appear to be fairly solid, the left-hand turns are almost wild.”

A YouTube video uploaded by user AI Addict shows some impressive navigation around parked vehicles and through intersections, but the car also makes a multitude of mistakes: During the drive the Tesla scrapes against a bush, takes the wrong lane after a turn, and heads directly for a parked car, among other problems. The software also occasionally disengages while driving, abruptly giving the driver the responsibility of driving.

“It’s hard to know just by watching these videos what the exact problem is, but just watching the videos it’s clear (that) it’s having an object detection and/or classification problem,” says Missy Cummings, an automation expert who is director of the Humans and Autonomy Laboratory at Duke University in Durham, N.C. In other words, she says, the car is struggling to determine what the objects it perceives are or what to do with that information, or both.

According to Cummings, it may be possible for Tesla to eventually build a self-driving car, but the amount of testing the automaker has done so far would be insufficient to build that capacity within the existing software. “I’m not going to rule out that at some point in the future that’s a possible event. But are they there now? No. Are they even close? No.”

Testing Without Consent

Cummings says that although Tesla’s approach of putting beta versions of software directly in the hands of consumers is common for computer software development, it could cause real problems on the road. “It’s a very Silicon Valley ethos to get your software 80 percent of the way there and then release it and then let your users figure out the problems,” she says. “And maybe that’s okay for your cell phone, but it’s not okay for a safety critical system.”

Reimer says he doesn’t think anyone on the road should be subjected to the risks of a test vehicle, but he told CR that he has noticed marked performance improvements between older and newer videos of Teslas automating driving tasks. “It is interesting how fast the engineers at Tesla appear to be using data to improve system performance,” he says.

But until Teslas become fully self-driving, such incremental improvements could make drivers less safe as they begin to rely on the car to make decisions for them, Fisher says. “When the software works well most of the time . . . a minor failure can become catastrophic because drivers will be more trusting of the system and less engaged when they need to be.”

To combat complacency, Fisher, Reimer, Talbott, and others have called for Tesla to incorporate robust driver monitoring systems that work in real time and ensure that the person behind the wheel is ready to take control as soon as the car cannot handle a driving task—a step Tesla has been reluctant to take in the past.

Unless Tesla changes course, its approach to automation may backfire, says Jason Levine, executive director of the Center for Auto Safety, a watchdog group. Levine says that automation can save lives, but not if its limitations aren’t made clear to drivers. “Vehicle manufacturers who choose to beta-test their unproven technology on both the owners of their vehicles and the general public without consent at best set back the cause of safety and at worst result in preventable crashes and deaths,” he told CR. In addition, Levine and others say Tesla’s use of marketing terms, such as “Full Self-Driving,” provide a false and deceptive impression that the vehicles can drive without human intervention.

AI Addict / YouTube AI Addict / YouTube

A Safer Approach?

Talbott, the American University professor, says that Tesla’s approach to testing software on public roads without any driver monitoring makes the automaker a “lone wolf” in what she otherwise considers a safe industry. “The rest of the industry says, ‘We want to get it right, we want confidence from the general public, we want regulators to be partners,’” says Talbott, who is also a former motor vehicle regulator and product liability attorney. So far, “getting it right” has meant the use of trained safety drivers and closed test courses to validate vehicle software before testing on public roads, she says.

CR spoke with representatives from Argo AI, Cruise, and Waymo, which are all testing self-driving car prototypes on public roads and working to create commercially available fully self-driving vehicles. Although none would comment on Tesla directly, all three pointed us to their own safety policies.

“Each change of our software undergoes a rigorous release process and is tested through a combination of simulation testing, closed-course testing, and driving on public roadways,” Waymo spokesperson Sandy Karp told CR.

Ray Wert at Cruise told CR that the company’s autonomous vehicles would be deployed only after the company is satisfied that the vehicles are safer than a human driver. “Our plan is to launch with communities, not at them,” he says. And an Argo AI representative pointed to the company’s extensive driver training and software development standards, which are all publicly available online.

Partners for Autonomous Vehicle Education (PAVE), an industry group, told CR that it supports the use of highly trained professional test safety operators and that using untrained safety drivers may jeopardize greater public acceptance of vehicle automation.

Ultimately, it may be up to federal regulators to determine what kinds of vehicle software can be used on public roads—a step that they’ve been reluctant to take so far. “I have never seen anything like we’re seeing today with Tesla, where it’s as if the U.S. Department of Transportation has blinders on when it comes to the actions of this particular company,” Talbott says.

But there have been some recent movements toward further regulation. For example, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has ordered new reporting requirements for vehicles involved in crashes while automation was in use.

“I am hopeful that the data will allow NHTSA to better monitor and manage automotive and technology companies working to perfect automation systems over the coming decades,” Reimer says.

Eventually, regulators will have to catch up with automakers’ plans to test rapidly evolving autonomous vehicle technology.

“Car technology is advancing really quickly, and automation has a lot of potential, but policymakers need to step up to get strong, sensible safety rules in place,” says William Wallace, manager of safety policy at CR. “Otherwise, some companies will just treat our public roads as if they were private proving grounds, with little holding them accountable for safety.”