Can Consumer Boycotts Actually Be Successful?

Activists are calling on everyone to stop buying for 24 hours to send a political message. If history is any indication, the economic blackout just might work.

Since at least 1773, when colonists threw a Tea Party in Boston Harbor to protest taxation without representation, American consumers and activism have gone back like babies with pacifiers. In 1955, Martin Luther King Jr. asked the Black residents of Montgomery, Ala., to stop taking the bus for civil rights. In 1965, Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez urged Americans not to buy grapes for farmworker rights.

And, on Feb. 28, 2025, John Schwarz wants you to keep your hands out of your pockets to support what he calls “the fight for economic freedom and justice.”

You may not have heard of Schwarz or The People’s Union USA, an “emerging” organization founded this year by the 57-year-old Queens, N.Y., native that bills itself as “a grassroots movement dedicated to economic resistance, government accountability, and corporate reform.”

But Schwarz’s call for a 24-hour economic blackout—from midnight on Thursday, Feb. 27, through midnight on Friday the 28th (all 24 hours of Feb. 28)—has been getting a lot of attention.

There are two ways you can mobilize: Through fear and through hope. Fear doesn’t encourage autonomy, but hope does. Boycotts say the power is with us.

Lecturer in Organizing and Civil Society at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University

Voting With Our Dollars

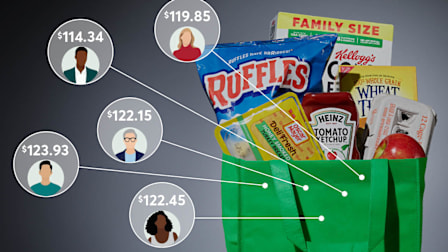

Consumers seem open to signing on. A nationally representative Harris poll found that more than 4 in 10 Americans have already shifted their spending over the last few months to align with their moral views. And while the latest retail boycotts may have been animated by opposition to recent moves by the Trump administration, the impulse generally appears to transcend party politics: The same Harris poll found that nearly as many Republicans (41 percent) and independents (40 percent) as Democrats (50 percent) have shifted their spending habits to align with their views.

“It’s a way for people to say I can’t vote until the off-year election so I’m going to take measures into my own hands along with other like-minded people,” says Lawrence Glickman, a professor of American Studies at Cornell University and author of “Buying Power: A History of Consumer Activism in America” (2009, University of Chicago Press). “A consumer boycott is a collective grassroots action to use economic levers to create some sort of political change,” he says.

What are the odds that The People’s Union USA boycott will have its intended effect?

That depends on how you define its goals. Historically, Glickman says, successful consumer boycotts have tended to fall into one of two categories. The first are hypertargeted boycotts focused on addressing specific grievances against companies serving a narrow group or local clientele. As examples, he points to a series of boycotts in 1880s New York City that saw union supporters refusing to patronize a particular bakery or saloon in their area until it hired union labor.

Schwarz’s national economic blackout is the other kind, Glickman says, where the aim isn’t a specific change but “raising political consciousness.”

Marshall Ganz is inclined to agree. In 1964, he left Harvard University a year before getting his undergrad degree to organize with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, registering Black citizens in Mississippi to vote. The next year, he joined the United Farm Workers, working alongside Cesar Chavez in the effort to unionize California farm workers.

“There are two ways you can mobilize: through fear and through hope," says Ganz, now a lecturer in Organizing and Civil Society at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “Fear doesn’t encourage autonomy, but hope does. Boycotts say the power is with us.”

Join the Consumer Movement

Protect your financial safety and save the CFPB.

Boycotts That Worked

Here are five examples of consumers using their buying power to make change.

1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott

The issue: A formal policy of racial segregation in the public transit system in Montgomery, Ala., forced Black passengers to surrender their seats to white passengers.

The ask: Courteous treatment by bus operators, seating on a first-come, first-served basis, and hiring Black bus operators on routes predominately taken by black passengers.

Photo: Don Cravens/Getty Images Photo: Don Cravens/Getty Images

The action: For 381 days, Black people in Montgomery walked, biked, and even rode horses and mules to reach their jobs and other necessary destinations. With Black passengers making up over 70 percent of the system’s ridership, the boycott put the system in financial distress. To help boycotting passengers get where they needed to go, more than 200 drivers volunteered their vehicles for car pools, and Black taxi drivers charged passengers only 10 cents a ride, the bus fare at the time.

The impact: The Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling that bus segregation violated the equal protection and due process clauses of the 14th Amendment. The decision desegregated Montgomery’s transit system and ended the bus boycott on Dec. 20, 1956.

1965 Delano Grape Strike

The issue: Table grape growers in California fought—sometimes violently—farmworker efforts to organize unions and negotiate collectively for higher wages and basic labor and safety protections.

The ask: Raise the average hourly wage from $1.25 to $1.40 and the piece rate from 10 cents to 25 cents per box of grapes packed, and establish that farmworkers were protected by the National Labor Relations Act and therefore had a right to bargain collectively.

Photo: Ted Streshinsky/Getty Images Photo: Ted Streshinsky/Getty Images

The action: Filipino farmworkers joined forces with the fledgling National Farm Workers Association, led by Cesar Chavez, in calling for a boycott of grape growers and their products, including alcohol. NFWA members and volunteers picketed retail stores selling non-union grapes and appealed to other unions to boycott the products as well.

The impact: By linking discrimination faced by farmworkers to discrimination against Black people, NFWA organizers were able to build on the gains of the Civil Rights Movement. The campaign drew widespread public support and chipped away at the demand for non-union-sourced grapes. After five years a collective bargaining agreement with major grape growers was reached, affecting more than 10,000 farm workers. NFWA co-founder Cesar Chavez called the public “our court of last resort.”

1973 Meat Boycott

The issue: Driven by a feed grain shortage and increased demand in the U.S. and abroad, meat prices began to soar in 1972.

The ask: Consumers demanded lower prices and called for President Richard Nixon to implement price controls and change farm and export policies.

Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

The action: During the first week of April 1973, housewives across the country stopped buying and cooking meat. Without a widely recognized national leader, decidedly decentralized campaign was spurred by small, mostly female-led consumer, women’s, and community groups, which staged marches and protests outside supermarkets. One group handed out peanut butter sandwiches at the city hall in White Plains, N.Y., to raise awareness.

The impact: Some retailers lowered prices in the short term, and Nixon announced on national TV that the federal government was imposing price ceilings on beef, pork, and lamb, “effective immediately.” The more lasting impact may have been in awakening homemakers to their collective power. One protestor told the New York Times: “Now we realize we have a lot of clout. We housewives can make our voices heard not only on this situation but others, too.”

1988 Tuna Boycott

The issue: Commercial tuna fishers chasing, netting, and killing dolphins to catch the schools of tuna that tend to follow them.

The ask: Reform fishing practices to eliminate the use of nets and fishing practices that trap and drown dolphins.

Photo: Getty Images Photo: Getty Images

The action: Biologist Samuel LaBudde went undercover as a cook on a fishing vessel and secretly recorded the deaths of hundreds of dolphins. LaBudde’s video generated passionate reactions around the world and, on April 11, 1988, helped launch a consumer boycott of tuna.

The impact: The boycott spurred the adoption of standards for dolphin-safe tuna, and three of America’s largest tuna companies—StarKist, Bumblebee, and Chicken of the Sea—agreed to stop purchasing, processing, and selling tuna caught by intentionally chasing and netting dolphins. The tuna boycott also highlighted the power of video to animate public action.

2023 Bud Light Boycott

The issue: Opposition to a Bud Light promotional video featuring Dylan Mulvaney, a transgender woman and social media influencer.

The ask: “They went woke. Now we should make sure they go broke," then Fox News pundit (and current U.S. Secretary of Defense) Pete Hegseth said of Bud Light manufacturer Anheuser-Busch at the time.

Photo: Natalie Behring/Getty Images Photo: Natalie Behring/Getty Images

The action: Conservative pundits, politicians, and celebrities publicly shunned Anheuser-Busch products. Musician Travis Tritt banned the products from his tour, for example, and fellow performer Kid Rock posted a video on social media in which he fired a machine gun at cases of Bud Light. Copycat videos quickly proliferated.

The impact: Anheuser-Busch’s annual revenue was reported to have fallen $1.4 billion in 2023. And in 2024, after more than two decades as the bestselling beer in the U.S., Bud Light was dethroned.

Did You Know: CR's Own History

For its part, Consumer Reports has taken a balanced approach to retail boycotts, championing the rights of consumers to vote with their pocketbooks while generally declining to pick sides—and focusing instead on giving consumers the information they need to make their own informed decisions.

But that balance hasn’t always been easy to maintain, says Norman Silber, a visiting professor of consumer law at Columbia Law School and a former board member (and historian) of Consumer Reports. In the lead-up to World War II, he says, the organization struggled with what to say when its testing found that most German and Japanese cameras were superior to their American counterparts. A decision was made to report the findings in full—but, Silber says, “a box ran next to the ratings urging consumers to sacrifice their desire for the best in order to serve ethical standards.”