What Is Really Going on With All This Radioactive Shrimp?

Here’s the latest on how shrimp and spices were contaminated with cesium-137, how the FDA responded, and why experts say consumers shouldn't panic

In August, the Food and Drug Administration issued an unusual warning: Don’t eat certain lots of frozen shrimp sold at Walmart because they might be radioactive. It didn’t take long for the list of recalled products to grow far beyond Walmart. Over the past six weeks, hundreds of thousands of pounds of frozen, raw, and cooked shrimp have been pulled from supermarket shelves across the U.S.

All of the affected shrimp share at least one thing in common: They were processed by an Indonesian firm known as Bahari Makmur Sejati, or BMS Foods. The company may not be well known to consumers, but from January to July, it was responsible for about a third of American shrimp imports from Indonesia—which itself is the third largest exporter of shrimp to the U.S., according to ImportGenius, a trade data analysis company.

BMS Foods caught the attention of regulators earlier this year after cesium-137 was detected in its shipping containers and shrimp at four U.S. ports. It’s a synthetic radioactive isotope that’s not typically found in food but can be detected by the monitoring systems at U.S. ports. It’s produced during nuclear fission—the process of splitting an atom’s nucleus—which is often used to generate power or for nuclear weapons.

Over the past month, an investigation by Indonesia’s nuclear agency has found evidence of widespread radioactive contamination in the area where the shrimp was packaged, a region of the island of Java known as the Cikande industrial area.

The situation is further complicated by the FDA’s September discovery of cesium-137 in a shipping container from Indonesia carrying cloves from a spice exporter over 400 miles away from the Cikande zone.

The levels of radioactivity detected in both the shrimp and the cloves aren’t high enough to pose any immediate risk to consumers, and Indonesian authorities have stated that the country’s exports are safe. But on Oct. 3, the FDA announced sweeping new import requirements for all shrimp and spices from the island of Java—which is home to about 150 million people—and a nearby region.

“There are more questions than answers at this point,” said Steven Biegalski, PhD, chair of the nuclear and radiological engineering and medical physics program at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

Here’s what we know so far.

How Concerned Should You Be About Radioactive Shrimp?

According to Biegalski, consumers in the U.S. have no reason to panic. The activity concentrations found in the shrimp and cloves samples tested by the FDA—68 and 732 becquerels per kilogram, respectively—are well below the FDA’s intervention level for cesium-137 contamination, which is 1,200 becquerels per kg.

What Exactly Is Cesium-137?

Cesium-137 is a radioactive isotope produced by nuclear fission, typically used in medical devices or the calibration of radiation-detection equipment like Geiger counters, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s also a byproduct of the processes used in nuclear weapons testing, the operation of nuclear reactors, and nuclear accidents. According to the CDC, people in the U.S. are exposed to low levels of cesium-137 on a daily basis because it’s present in the environment from weapons testing in the 1950s and 60s.

Cesium-137 can take decades to break down in the environment, but the body processes it much faster. Ingested cesium is typically absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestines. In an adult, about 10 percent of ingested cesium-137 is excreted from the body in a matter of days. The other 90 percent has a biological half-life of 110 days, meaning the human body naturally eliminates half of what remains within about four months.

How Did Indonesian Shrimp and Cloves Get Contaminated?

It’s not totally clear, but preliminary evidence suggests it’s because of industrial activity near food processing facilities rather than anything in the water or soil.

Officials from Indonesia’s nuclear energy regulatory agency have traced the source of contamination to a steel manufacturer in the Cikande industrial area known as Peter Metal Technology, or PMT. Some of the highest levels of contamination detected in the area were reportedly found in the company’s furnace, which is about 1.5 miles southwest of the BMS Foods facility where the shrimp was processed.

Investigators think that radioactive dust was released into the environment after PMT inadvertently smelted scrap metal containing cesium-137. “Because it’s airborne, the contamination can be carried by wind,” said Bara Khrishna Hasibuan, a senior adviser to Indonesia’s Ministry of Food Affairs, at a Sept. 30 press conference.

Scrap metal was commonly used as a raw material by PMT, according to the Indonesian outlet Antara News. It’s unclear how it may have become contaminated with cesium-137. Biegalski, whose area of expertise includes nuclear forensics, told CR that the “easiest explanation” is that a medical or industrial device containing cesium-137 was inadvertently reprocessed as scrap metal. The radioactive material could have become gaseous after entering the PMT furnace and then been released from the facility’s smokestack, he said.

“That whole island likely had a cesium-137 plume go over it, leaving a trail of contamination,” Biegalski said. The Indonesian government is reportedly now considering new regulations on scrap metal to reduce the risk of further contamination.

The release of a radioactive plume could explain the pattern of contamination in the area, according to Biegalski. Officials have detected elevated radiation levels in at least 10 sites within a roughly 3-mile radius of PMT so far, including the BMS Foods facility, and they’re working to decontaminate the region, a process authorities estimate will take several months.

The question of how the cloves were contaminated is harder to answer. The facility where they were processed is over 400 miles away from the smelter. Yet the radiation levels in the sample tested by the FDA were 10 times higher than those found in the shrimp. More perplexing still, a preliminary investigation found only normal background levels of radiation at the facility that processed the cloves, according to Antara News.

“There are a lot of plausible scenarios here,” Biegalski said. “We don’t know where the [cloves] contamination occurred. It could have happened during transit, or it could have happened as an airborne plume, where things got picked up one day but didn’t necessarily gravitationally settle.” The plume could have also settled on the field where the cloves were grown or on the containers they were transported in, he suggested. But there are no clear answers yet.

What Is the FDA Doing?

On Aug. 14, the agency placed BMS Foods on its import alert “red list,” effectively barring all of the company’s shrimp products from entering the U.S. until the problem is resolved. About a month later, it did the same to Natural Java Spice, the company responsible for the contaminated cloves.

The Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration has sent emergency teams to U.S. ports to evaluate the extent of cesium-137 contamination, an agency spokesperson told CR. Officials from the International Atomic Energy Agency have also been in close contact with Indonesian authorities, who are monitoring the situation, said Joanne Liou, a spokesperson, in an email.

On Friday, the FDA announced that starting Oct. 31, it will require import certification for all shrimp and spices from the island of Java as well as from Lampung province in Sumatra, northwest of the Cikande industrial area. Notably, this is the first time the agency has exercised this authority. The move extends similar restrictions to all regional exporters, who will be required to obtain shipment-by-shipment certification from the Indonesian government attesting that their products are free from radioactive contamination in order to be accepted at U.S. ports.

“This is a good effort to try to stop the hemorrhaging of trust,” said Darin Detwiler, an associate professor at Northeastern University who has researched the FDA’s implementation of food safety policies. But he cautioned that this effort, like others in the agency’s past, could upset the balance of trade between the U.S. and Indonesia by introducing unnecessary barriers for exporters unaffected by the contamination.

“Consumers need to have trust in their [food] sources,” Detwiler said. “But we also need to look beyond the surface.” Over the past six weeks, elected officials and lobbying groups have used the spate of radiation-related recalls to advocate for policies restricting foreign imports.

Biegalski thinks that the FDA’s decision is reasonable and likely stems from concern over whether products with even higher levels of radioactivity than what’s been detected so far could inadvertently enter the supply chain. “We don’t want to scare the public over things that really are benign at this point,” he said, “but it would also be irresponsible if we didn’t continue due diligence and monitor what is coming in from the region.”

What Should Consumers Do?

The FDA says no products that tested positive for cesium-137 have entered the U.S. marketplace, and the levels found in the shrimp and clove samples rejected at U.S. ports are too low to cause acute harm.

Out of an abundance of caution, the agency has issued recalls for all products from BMS Foods that entered the U.S. after cesium-137 was first detected in shrimp. See this up-to-date list of the affected products and brands on the FDA website.

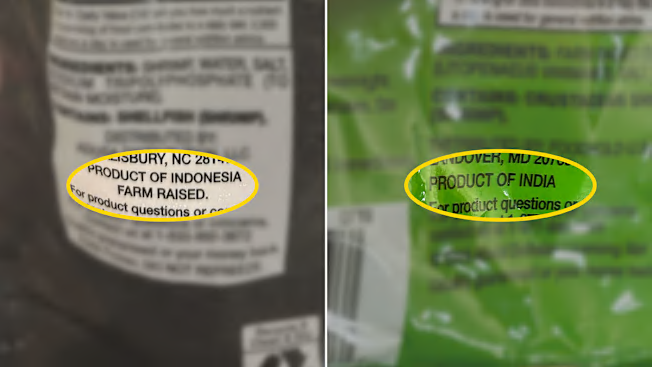

If you aren’t sure whether a product you’ve purchased is involved in the recall, check the packaging to see whether it lists a country of origin, said James E. Rogers, PhD, director of product and food safety research at CR. Food items will often include an “imported from” or “product of” disclosure on the packaging label near the ingredients list or nutrition facts box.

“If you don’t feel confident or safe eating a product,” Rogers said, “throw it out.”

Photos: Consumer Reports Photos: Consumer Reports