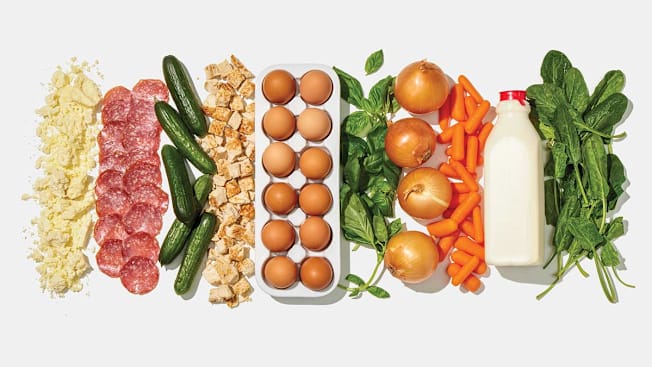

10 Really Risky Foods Right Now

Eggs. Deli meat. Onions. These are just a few of the staples that have been making millions sick. Here, how to eat these everyday foods again—and stay safe.

If it seems like every time you check the news there’s yet another recall or alert about large numbers of people getting sick from eating a particular food, you’re not imagining things.

There was a 41 percent jump in food recalls due to possible contamination with salmonella, E. coli, and listeria in 2024 compared with the year before, according to the U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund. The recalls involved foods from iconic brands like Boar’s Head and McDonald’s, as well as everyday staples like carrots and cucumbers. Confirmed cases of foodborne illness rose by 20 percent, and related hospitalizations and deaths more than doubled. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that tens of millions of Americans are sickened annually by foodborne bacteria.

The Most Common Causes of Food Poisoning

Although all bacteria responsible for foodborne illness cause similar symptoms, there are important differences in their prevalence, how they affect the body, and the risks they pose. These three are most commonly involved in outbreaks.

Salmonella sickens an estimated 1.35 million people per year. The bacteria destroy the cells that line your intestines, causing stomach cramps, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea starting 6 hours to six days after exposure. In some cases, the infection can spread to the bloodstream, triggering even more severe illness. Severe cases may require antibiotics. If the infection spreads beyond the intestines and into the bloodstream, or if a person is severely dehydrated, hospitalization may be necessary.

E. coli causes about 265,000 illnesses annually. The most dangerous types of E. coli are called STEC, for Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, which includes the O157:H7 strain that has been responsible for many outbreaks. Signs of an STEC infection are watery, often bloody, diarrhea; stomach cramps; and a low-grade fever. Symptoms can start three to five days after exposure, and begin to improve after about a week. But at this stage, some people develop potentially life-threatening kidney damage. Signs include decreased urination, extreme fatigue, and paleness in the cheeks and inside the lower eyelids. Staying hydrated is key and can lessen the chance of kidney damage. Antibiotics aren’t used because they raise the risk of kidney problems.

Listeria monocytogenes causes just 1,600 illnesses a year. One reason is that most people’s immune systems are strong enough to combat listeria before it makes them sick. When illness does occur, usually within two weeks of exposure, symptoms can range from fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and muscle aches that last a few days to potentially life-threatening damage to the brain and spinal cord. Very young children, people 65 and older, and those with compromised immune systems are more likely to get a listeria infection and become very ill. Listeria can also cause miscarriage, stillbirth, or serious illness in a newborn, even if the pregnant person doesn’t get sick. Antibiotics are used for serious illnesses, and IV antibiotics for those who are pregnant.

In many instances, a case of foodborne illness will resolve on its own. But see a doctor if you have a fever above 101° F or you’re unable to keep liquids in your system for two or three days, which could put you at risk for dehydration.

10 Risky Foods of 2024

This is a ranking of the food recalls and outbreaks due to bacterial contamination that occurred or ended in 2024. The data are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Department of Agriculture.

Why it’s risky: Given the safety challenges associated with deli meat, it’s no wonder that it has consistently appeared on CR’s risky foods lists. Bacteria, especially listeria, are often found in processing plants and on slicers and other equipment at deli counters. The meat is cooked and then kept cold, but it’s handled frequently (increasing the chances of cross-contamination) and listeria can survive and grow in cold temperatures. Problems with listeria in liverwurst at a Boar’s Head plant led to the largest outbreak of foodborne illness in 2024. The company recalled 7 million pounds of cold cuts of all types and announced it would no longer make liverwurst. A separate recall of underprocessed coppa (dried cured meat) from Busseto Foods Charcuterie is a reminder that listeria isn’t the only concern with processed meats. The meat, which was sold under various brand names, was linked to salmonella infections in 33 states.

Protect yourself: Heating deli meat until it’s piping hot is the only way to get rid of any harmful bacteria that’s present. If that’s not practical, people at high risk for a serious listeria infection—those who are pregnant, are under age 5 or over age 65, or have a weakened immune system due to a condition like cancer—should consider skipping deli meat, CR’s Rogers says. For others, prepackaged cold cuts may be a somewhat safer option. They’re handled less than meat sliced at the counter, and there’s evidence suggesting they’re less likely to cause listeria infection.

Why they’re risky: Like other vegetables that have made people sick over the years, cucumbers are sometimes contaminated by bacteria from animal waste in the soil or irrigation water, often from runoff from nearby livestock. The first cucumber outbreak in 2024 involved whole cucumbers sold at supermarkets. The second was linked to sliced cucumbers in prepared foods like salads and vegetable trays sold at most major U.S. grocers.

Protect yourself: Choose fruits and vegetables that are free of bruises or damaged skin because bacteria can more easily enter those areas. Washing and peeling can reduce bacteria but doesn’t remove all of it.

Why they’re risky: Bacteria in milk can come from the animal itself or be introduced during milking and processing. Pasteurization—heating milk to 161° F—kills bacteria and the bird flu virus that has been found in raw milk. In 2024, unpasteurized (raw) milk products from Raw Farms were linked to two separate outbreaks—one for salmonella in milk and cream, and the other for E. coli in raw cheddar cheese.

Protect yourself: Don’t drink raw milk. As for raw milk cheese, the Food and Drug Administration requires that it be aged for at least 60 days before it’s sold, which should destroy any harmful bacteria. But as last year’s outbreak shows, there are no guarantees, so those at high risk may want to stick with cheese made from pasteurized milk.

Why they’re risky: Soft cheeses are another repeat offender on CR’s risky foods lists. Their high water content and low acidity allow listeria to thrive. The source of a nearly decade-long listeria outbreak was finally revealed last year when a routine test at Rizo-López Foods detected listeria in its cotija and queso fresco. The company recalled these and other dairy products produced at the same facility. The same strain was eventually linked to illnesses across 11 states.

Protect yourself: Avoid these and other soft cheeses like Brie unless they’ve been cooked as part of a recipe, such as a casserole. Instead, stick with hard cheeses like cheddar, Gouda, Parmesan, pecorino, or Gruyère, especially if your immune system is weakened due to an illness like cancer or other chronic conditions, or if you’re pregnant. Hard cheeses have a lower water content and are less hospitable to listeria. Wash your hands after handling soft cheese.

Why they’re risky: Salmonella can contaminate the inside of an egg during development and the shell as it is laid. Last year, Milo’s Poultry Farms recalled millions of eggs because they were linked to a salmonella outbreak that sickened people in 12 states. Another large recall involved organic eggs produced by Handsome Brook Farms shipped to Costco stores nationwide, although no salmonella illnesses related to these eggs were reported.

Protect yourself: Throw away any eggs with broken shells. Wash your hands after handling eggs, but don’t wash the eggs. Doing so can spread salmonella from the shell to the inside of the egg. To kill all bacteria, cook eggs until both the yolk and the white are firm. Scrambled eggs should not be runny. Use pasteurized eggs or a liquid egg product when making dishes that call for raw or undercooked eggs, such as a Caesar salad dressing.

Why they’re risky: Exposure to contaminated soil or irrigation water can make onions unsafe to eat raw. They’ve been involved in several outbreaks over the years. Last fall, investigators determined that nearly all of the people sickened in an E. coli outbreak had eaten McDonald’s Quarter Pounders containing fresh, slivered yellow onions supplied by Taylor Farms. The company then recalled all of the affected onions.

Protect yourself: While you can’t do much about the ingredients restaurants use, for meals at home, buy whole, unbruised produce and cut it up yourself. (Slicing, chopping, and other processing in commercial kitchens can increase the chances of spreading bacteria.) When using raw onions, discard the first few layers before slicing; the inner layers are less likely to be contaminated.

Why they’re risky: As with other types of produce, many of the leafy greens in the U.S. are grown on farms that are located close to cattle feed lots. Irrigation water contaminated by runoff from those lots has been the source of several outbreaks. Last year, fresh spinach and a romaine-iceberg lettuce mix that was shipped to restaurants, schools, and caterers caused two E. coli outbreaks.

Protect yourself: If you’re in a high-risk group, consider skipping salads or raw greens on sandwiches when dining out. At home, you can lower the risk of illness by using hydroponic lettuce, which is grown in greenhouses and therefore less likely to be contaminated by animal waste. When using whole heads of lettuce, remove and discard the outer leaves; the inner leaves are less exposed to sources of contamination.

Why they’re risky: Organic produce can also become contaminated with bacteria picked up in a field or processing plant. Grimmway Farms, one of the largest carrot producers, recalled organic bagged whole and baby carrots sold under more than a dozen brand names, including Bunny-Luv and 365 Whole Foods Market, after they were connected to E. coli illnesses in 19 states.

Protect yourself: Cooking is your safest bet for veggies that can be eaten raw or cooked. Washing and peeling can reduce bacteria but doesn’t remove all of it.

Why it’s risky: Like other greens, fresh herbs are susceptible to contamination from soil, and they’re often eaten raw. In this outbreak, various brands of packaged organic basil produced by Infinite Herbs were connected to a salmonella outbreak in 14 states.

Protect yourself: Rinse herbs well before using them. Cooking herbs in whatever dish you’re making rather than adding them raw before serving is the safest way to eat them, CR’s Rogers says.

Why they’re risky: Poultry and meat can present a risk of foodborne illness even if it was already cooked when you bought it. Prepared foods go through many processing steps, each of which exposes them to a risk of contamination. In this case, routine testing by federal health officials found listeria in cooked poultry from BrucePac, leading to a recall of nearly 12 million pounds of ready-to-eat meat and poultry that had been used in hundreds of prepared foods, including salads and fresh and frozen burritos.

Protect yourself: Thoroughly heat frozen foods. When buying salads and sandwiches that contain cooked meat, be sure they are refrigerated when you buy them and keep them cold until you’re ready to eat them. That can slow the growth of listeria and other harmful bacteria.

5 More Foods That Can Make You Sick

These foods have caused several outbreaks in the past, so it makes sense to be aware of the risk they pose and be careful when handling and eating them.

Sprouts

The seeds used to grow alfalfa and bean sprouts can be tainted with bacteria from the soil. They are also sprouted in water in warm, humid environments—ideal conditions for germ growth. Avoid eating raw sprouts. Instead, cook them to kill any bacteria.

Raw Shellfish

Shellfish—like oysters and clams—can be contaminated with bacteria such as vibrio, which naturally occurs in coastal waters, and norovirus, which is typically from untreated human sewage. Both cause vomiting and diarrhea, and norovirus also easily spreads from person to person. Cook shellfish to 145° F. Discard any with open shells before cooking or closed shells after cooking.

Ground Meat and Poultry

Cooking is likely to kill surface bacteria on whole cuts like steak or chicken breast. But grinding mixes surface bacteria throughout the meat, making thorough cooking even more important. It also brings meat into contact with equipment that could be contaminated. Cook ground meat to a minimum internal temperature of 160° F, ground poultry to 165° F.

Uncooked Flour

Wheat can be contaminated with bacteria from wild animal droppings or when it’s grown in fields near livestock. The milling process doesn’t kill bacteria. Don’t eat raw batter or dough. (Raw cookie dough in commercial ice cream is most likely safe.) When cooking with raw flour, take care that it doesn’t come into contact with foods you will be eating raw.

Unpasteurized Juice and Cider

Most juice sold in the U.S. is pasteurized to kill bacteria, but some juice bars, farmers markets, or health food stores sell juices that aren’t pasteurized. That puts you at risk from harmful bacteria that might have been in the fruit or vegetable. Consume only pasteurized juices.

How an Outbreak Happens

Here’s a brief overview showing the steps in identifying the source of contaminated food and how the details are communicated to consumers.

Harmful bacteria that animals carry in their gut can contaminate meat during slaughter or processing. The bacteria can spread to fruits and vegetables when soil or irrigation water is polluted by animal waste. Bacteria can also get into food during harvesting, transport, or processing.

It can be sold directly to shoppers at the supermarket or used as an ingredient in other foods they buy, like prepared salads or frozen meals. Restaurants or cafeterias may also serve the contaminated food.

Most sick people recover on their own, and the illness is never reported. Others may seek medical attention and be tested for foodborne illness. When a test is positive, state health officials share results with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and collect information, including foods the sick person recently ate.

When multiple people are sickened, CDC researchers try to match the bacteria’s DNA “fingerprint” to other confirmed cases, which may be spread across several states. This process can take weeks or even months.

When investigators can identify a source, they alert the company and encourage it to recall the product. (Federal and state authorities can’t usually require a business to issue a recall, but most typically comply with a request.)

The company asks retailers to remove the item and warns restaurants and cafeterias not to use it. The media alerts consumers to throw out or return recalled food they may have purchased. (Some retailers directly notify customers who bought the recalled items.)

Illustrations by The Tom Agency

How to Protect Yourself

"Following a few simple food prep precautions at home can dramatically reduce your risk of foodborne illness," says James E. Rogers, PhD, director and head of product and food safety testing at CR. That’s important because in your kitchen, bad bacteria can easily spread from surface to surface, and from your hands to anything you touch. What’s more, certain bacteria, like listeria, can continue to survive in warm or cold environments, even the freezer. There are also a few easy but effective strategies to use when grocery shopping or eating away from home. Safety experts recommend you take the following steps:

Cook food to a safe temperature. Cook poultry and reheat leftovers to at least 165° F; ground meat and sausage to at least 160° F; and steaks, roasts, and chops of any kind to at least 145° F. Never guess: Use a meat thermometer to check. At restaurants avoid ordering burgers and steaks rare or medium rare.

Double up on cutting boards and knives. This reduces the risk of spreading bacteria from raw meat or poultry to vegetables or other foods. For meat, consider a silicone board rather than wood, which has grooves where bacteria may hide even after cleaning.

Sanitize countertops. After food prep, clean the counter with warm, soapy water and wipe with a paper towel or a kitchen cloth that you can launder before using again. Then sanitize using a solution of 1 tablespoon bleach to 1 gallon of water or with a commercial kitchen sanitizer. Pour or spray the bleach solution on surfaces and wipe dry with a paper towel or a clean kitchen cloth. If using a commercial kitchen sanitizer, follow label directions.

Practice sink safety. Do not rinse raw meat. It’s unnecessary and can spread dangerous bacteria to your sink and to other foods. Use a paper towel to turn the faucet on and off. Wash your hands after handling any raw meats or fish. Clean the sink daily using the same method recommended for your countertops.

Reduce refrigerator risks. Keep meat and poultry on the bottom shelf, where it’s coldest. (Check out more food storage safety tips.) Store them in the original packaging and on a plate or in a bowl to catch any drippings. Clean up spills immediately, and thoroughly clean shelves, drawers, and walls at least once a month. Use hot water and a mild liquid dishwashing detergent. Rinse. Then disinfect with a solution of 1 tablespoon bleach to 1 gallon water. Dry with a clean cloth or paper towel.

Put food away promptly. Perishable foods—like cheese, salads, cut veggies or fruit, or cooked meat—should not sit out unrefrigerated for longer than 2 hours (1 hour if it is hot outside). That goes for foods you might put out for a party or a picnic, or foods you have left over after eating a meal.

Buy whole fruits and vegetables. Precut packaged produce is processed in commercial kitchens, where cross-contamination may be common. Check fresh produce for bruises or cuts—that’s how bacteria can get in.

Shop refrigerated and frozen foods last. To protect your hands and other foods from potentially harmful bacteria, use an inside-out produce bag to pick up packages of raw meat, poultry, and fish, then turn it right side out around the item. Pack raw meat in a separate shopping bag from other foods. If you use cloth bags, be sure to wash them often and in hot water.

Demand a Safer U.S. Food Supply

"Maintaining a safe food supply is a fundamental public health priority," says Brian Ronholm, director of food policy at CR. To do that, these improvements to the food production and distribution system must be made.

Make the recall process faster. Ronholm says it’s vital that the Food and Drug Administration continue to move forward with its Food Traceability Rule, set to take effect in 2026. The rule mandates that companies maintain records that contain key data and tracking information to increase the speed of recalls.

Keep bad bacteria out of our food. CR has long pushed for the Department of Agriculture to declare salmonella in poultry an adulterant so that it could not legally be sold to consumers. (The USDA has already made this move for salmonella found in raw stuffed and breaded chicken breasts sold frozen.)

Adequately fund state and federal health departments responsible for tracking recalls and outbreaks. "An under-resourced food safety agency could jeopardize the stated objectives of the Make America Healthy Again initiative to improve the food system for children and adults," says Ronholm.

Want to get involved? Sign our petition calling for adequate funding of our food safety system.

Editor’s Note: This article also appeared in the May/June 2025 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.