How to Monitor Air Quality to Stay Safe From Health Risks

Use EPA notices, commercial apps, and even your own sensors to plan activities, especially if you have respiratory or other medical conditions

Smoke and soot from wildfires are darkening skies across the Eastern U.S., bringing deeply unhealthy air from Canada into some of the most populous parts of the U.S.

But it’s not always so obvious when the air isn’t safe to breathe. Invisible, odorless pollutants can linger in the air, causing discomfort for everyone and worsening symptoms for people with asthma and other respiratory diseases. In some areas, air pollution is a regular problem because of traffic or weather patterns.

Even when pollution is invisible, air quality sensors maintained by the Environmental Protection Agency or other organizations can tell you what air quality is like right now, and some services even predict what it’ll be like in the coming hours and days.

In most places, the gold standard for air quality data is the EPA’s AirNow program. It uses sensitive pollution sensors placed around the country to build an Air Quality Index, or AQI, for your location.

AirNow displays the current AQI, a number between 0 and 500 that tells you how safe it is to breathe the air outside. The numbers are divided into bands, which come with recommendations for how to stay safe. For particulate pollution—made of microscopic debris such as soot and dust—here are the EPA’s category bands and recommendations:

Check CR’s recommendations for the best air purifiers and air filters if wildfire smoke is affecting the air quality where you live.

More Ways to Keep Tabs on Pollution

The EPA’s AirNow calculations are an excellent source of air quality information for people who live near an AirNow sensor. However, large swaths of people don’t have a sensor nearby.

For people who don’t live near a sensor, there are several alternative sources of information that use different types of data to estimate air quality in the U.S., and around the world.

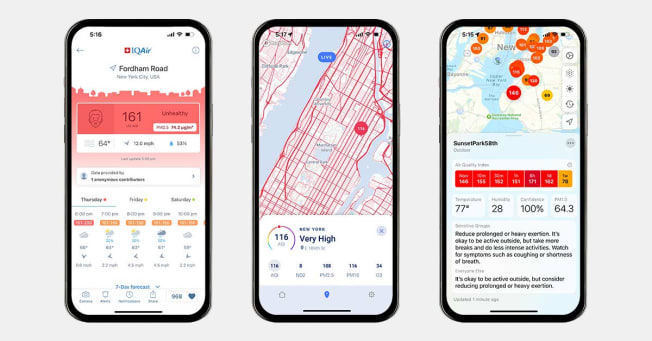

Source: AirVisual, Plume Labs, and Purple Air Source: AirVisual, Plume Labs, and Purple Air

AirVisual, an app from the Swiss company IQAir, uses data from government sensors, private sensors, and satellite imagery to estimate real-time AQI values and provide health recommendations. It also gives seven days of weather and air pollution forecasts, and can alert you when the air quality near you is either improving or getting worse. (IQAir sells monitors, air purifiers, and face masks, but its air quality app is free.)

Plume Labs, an app from the weather-prediction company AccuWeather, also provides real-time and forecasted AQI numbers using on-the-ground sensors and satellite imagery.

PurpleAir, a company that manufactures consumer-grade air quality sensors for indoor and outdoor sensing, makes data from most PurpleAir monitors available publicly on a map that also shows some historic data. These devices aren’t as accurate as the government’s high-quality sensors, but in certain cities, they are so densely packed that they can show small differences in air quality between one end of the city and the other.

If you want to know what the air quality is like in your own home, or right outside of it, you can purchase a sensor from a company like IQAir or PurpleAir. These sensors can help you understand the air you’re breathing and to take action, and they can add to the public network of sensors that others can access. Having your own sensor might be especially helpful if you’re particularly sensitive to air pollution.

What to Do When Air Quality Is Bad

When the air isn’t healthy to breathe, the EPA says you should consider reducing the intensity or length of your outdoor activities, staying away from busy roads where vehicles are creating even more pollution, and possibly delaying outdoor activities until the air quality gets better.

Here are a few more things you can do to keep you and your family safe when pollution levels are high.

Follow the EPA’s specific recommendations. If AQI levels are elevated, take a look at what the EPA suggests you should do, and cut back on outdoor activities if recommended.

When pollution levels are high, stay inside. Close your doors and windows—weather stripping and even duct tape can help create a good seal. Avoid burning anything indoors, including wood in fireplaces and wood stoves, cigarettes, and even candles. And spend your time away from rooms with ducts that are open to the outside, like laundry rooms and bathrooms.

Run an air purifier. These machines suck in dirty air and trap tiny particulate pollution before circulating cleaner air back into your home. CR has tested almost 150 air purifiers and has recommendations for the models that work best on wildfire smoke.

Add a HEPA air filter to your HVAC system. You can also upgrade your furnace or central AC filter so that it acts as a whole-home air purifier. Start by considering CR’s top-rated HVAC filters.

Wear an N95 mask if you’re going outside. The same masks that provide the best protection from COVID-19 also filter out other microscopic particles from the air, such as wildfire smoke and soot. It’s a great way to filter the air you’re breathing if you have to go outside when pollution is really bad.