How to Keep Your Vision Sharp

Cataracts, dry eyes, glaucoma, and other eye problems become more common with age. But these can be treated—and sometimes even cured—if you know the early signs and act fast.

In life, few things are certain. But one is: It becomes harder to see well as you age. “There are three things we cannot avoid: death, taxes, and presbyopia, the gradual loss of the ability to read up close,” says Nicole Bajic, MD, an ophthalmologist at the Cleveland Clinic.

The need for reading glasses is just one of many vision changes we may experience. But later-in-life eyesight issues can often be treated or cured, says Joshua Ehrlich, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology, and visual sciences and research associate professor in the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Cataracts

This clouding of the normally clear lens that’s behind your pupil can make the world look blurry, hazy, and less colorful.

The right treatment: Everyone is likely to develop cataracts in later life. But family history and conditions such as diabetes make them more likely, as do eye injuries, smoking, steroids, and exposure to sunlight without UV-protective sunglasses.

Signs and symptoms: They include blurry vision, light and glare sensitivity, difficulty seeing (and driving) in low light, and bright colors appearing faded. An optometrist or ophthalmologist can diagnose cataracts during an exam, and monitor them until they affect vision enough to need to be treated.

The right treatment: A common outpatient surgery—performed over 3 million times a year in the U.S.—involves swapping out the cloudy lens for a new, artificial one.

Diabetic Retinopathy

Over time, high blood sugar can damage retinal blood vessels. This can cause swelling in the retina and macula, a common cause of vision loss. Later, this can lead to the growth of new abnormal blood vessels in the retina, which can bleed, affect vision, and potentially cause a detached retina—a medical emergency. (See “How to Spot an Eye Emergency,” below.)

Who’s at risk: People with diabetes, especially if their blood sugar is not well controlled. And the longer you’ve had diabetes, the higher your risk. Retinopathy can also affect people with other chronic conditions, such as hypertension. Controlling blood pressure and cholesterol can reduce risk.

Signs and symptoms: Often none at first. Eventually, blurry vision or vision that alternates between blurry and clear, floaters (tiny specks in your vision), poor night vision, and blank or dark areas in your view.

The right treatment: Controlling high blood sugar is most important, and can often prevent vision loss. Certain people are candidates for injections in the eye to reduce swelling in the retina and macula, primarily with the same anti-VEGF drugs also used to treat wet AMD.

Droopy Eyelids

Excess skin (dermatochalasis) or muscle weakness (ptosis) can lead to difficulty fully opening the upper eyelid.

Who’s at risk: Aging can lead to loose skin that forces the eyelid to droop, and aging or injury can stretch or damage the levator muscle, which lifts up the eyelid. Both of these issues typically arise between ages 50 and 70.

Signs and symptoms: Difficulty fully opening your eyes, which can block vision. An ophthalmologist will do an exam and may use imaging tests to identify the cause.

The right treatment: Prescription eye drops that temporarily improve eyelid muscle function are used to manage some cases of ptosis, while surgery is often used to remove excess skin or strengthen or reattach the levator muscle. Insurance may cover surgery that is deemed medically necessary.

Dry Eyes

Tears help keep your eyes moist and clean, but some people don’t produce enough, or their tears evaporate too quickly. Untreated, severe “dry eye” can lead to corneal ulcers or abrasion on the cornea.

Who’s at risk: Anyone can develop dry eye, but it’s more common in women, especially after menopause. Certain prescription medications, including blood pressure and allergy drugs, may also cause dry eye, and over-the-counter decongestant eye drops marketed to reduce redness may worsen it over time.

Signs and symptoms: Eye irritation, discomfort, and redness; a stinging, burning, or scratchy sensation; blurred vision while reading; and paradoxically, an overload of tears—as your eyes try to compensate.

The right treatment: Over-the-counter artificial tears may provide enough lubrication. But some people need prescription eye drops that increase tear production, tiny plugs to slow or stop tears from draining, or surgery to seal the puncta (tiny openings that drain tears).

Glaucoma

A clear liquid called aqueous humor—which nourishes the eye and keeps it inflated—constantly flows into and drains out of your eye through an area between your iris and your cornea. With glaucoma, this fluid doesn’t drain as fast as it’s produced, allowing pressure in the eye to build up over time and damage the optic nerve.

Who’s at risk: The likelihood starts to rise after age 40, especially if you have high eye pressure, diabetes, or hypertension; you use steroids long-term; or you’ve had a previous eye injury. Family history plays a role, and people of African, Hispanic, or Asian heritage are at higher risk.

Signs and symptoms: Vision loss that usually starts from the periphery. Some people don’t notice glaucoma until they’ve lost nearly all vision, and early treatment can slow or stop disease progression—one reason regular eye exams are essential. The uncommon narrow-angle form of glaucoma, which is accompanied by sudden vision changes and severe pain, is an emergency. (See “How to Spot an Eye Emergency,” below.)

The right treatment: Prescription eye drops to help manage the production and drainage of fluid from the eye can sufficiently lower eye pressure for some people. Laser therapy is another potential first-line treatment. Surgery to improve the eyes’ drainage system is more invasive but can be the most effective way to control eye pressure.

Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD)

The vitreous, a clear, jellylike substance that fills the back of the eye, is attached to the retina by tiny fibers. Over time, the vitreous becomes less solid, and can pull away from the retina.

Who’s at risk: This happens to most people by age 70. It’s more common among people who are nearsighted, have had eye surgery, or have cataracts or diabetes.

Signs and symptoms: Flashes of light or floaters, which are tiny specks, lines, or circles in your field of vision. Sometimes, people experience a shadow, curtain, or streak of light moving across their vision, which may indicate an emergency. (See “How to Spot an Eye Emergency,” below.)

The right treatment: This is typically benign, and floaters and flashes usually become less noticeable over time on their own. Laser therapy or surgery is generally not recommended. But see an eye doctor as soon as possible if you have symptoms: In some cases, PVD can lead to a retinal tear or detachment, which requires immediate treatment.

Retinal Detachment

The vitreous can stick to the retina and pull on it. If the retina tears or detaches from the back of the eye, this can cause permanent vision loss. It requires urgent attention.

Who’s at risk: People with prior eye surgery or eye injuries, nearsightedness, a previous retinal tear or detachment in the other eye, or weak areas in the retina that an eye doctor has noticed in a previous exam.

Signs and symptoms: Flashing lights that can look like shooting stars, many sudden new floaters, or a shadow or curtain over all or part of your vision.

The right treatment: Act fast. Go to the emergency room if you can’t see an ophthalmologist or optometrist right away. An examination will reveal what the best treatment is for you. The options include laser therapy (which can sometimes seal tears or breaks) and surgery to reattach the retina.

How to Spot an Eye Emergency

While certain eye problems progress over time, others may be fast-moving and need immediate care. A case in point is narrow-angle or angle-closure glaucoma—which can cause vision loss within hours. This can be “exquisitely painful” in and around the eye and is often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, Ehrlich says. If you experience these symptoms, head to the emergency room, unless you can be seen immediately by an ophthalmologist.

In general, you should call an eye doctor or go to the ER right away if you notice any abrupt, dramatic vision change or experience physical trauma to your eye, Bajic says. Vision changes that call for fast action include sudden vision loss, blurriness, a shower of floaters, a curtain or shade across your sight, double vision, and severe pain in the eye, especially if it’s accompanied by nausea or headache.

CR Rates Eyewear Stores

See our ratings of eyeglass retailers and eyeglass and contact lens buying guide.

The Two Eye Tests You Really Need

There’s good reason—beyond updating a glasses prescription—to get routine eye exams: If something’s wrong, your doctor will almost always be able to see it. “Many diseases of the eye are diseases of architecture,” Andreoli says. Here, two tests everyone generally must have along with a basic exam.

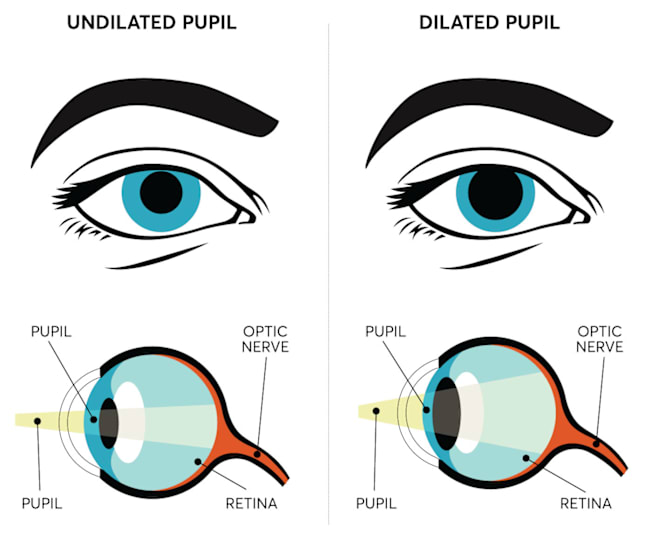

Dilated Eye Exam

A dilated eye exam uses special eye drops to open up your pupil and let more light into your eye. This allows your provider to see what’s happening inside your eye, often before you notice any changes to your vision, Andreoli says. It can give your doctor a good sense of your eye’s health because it provides a full view of the retina and optic nerve. And it’s the best way to detect diseases such as macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy early on. Some people who don’t want to have their eyes temporarily dilated may be offered what’s called retinal imaging—a photographic exam of the back of their eye. But retinal imaging is not a replacement for a dilated eye exam, and it can miss certain problems.

Eye Pressure Check

In this test, your doctor will numb your eye with drops, then use a device to check the pressure inside your eye and monitor for glaucoma. Initial glaucoma changes are often very subtle, but detecting and treating them early can prevent later vision loss.

Editor’s Note: This article also appeared in the November/December 2024 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.