Protein Powders and Shakes Contain High Levels of Lead

Protein supplements are wildly popular, but CR’s tests of 23 products found that more than two-thirds of them contain more lead in a single serving than our experts say is safe to have in a day

Much has changed since Consumer Reports first tested protein powders and shakes. Over the past 15 years, Americans’ obsession with protein has transformed what had been a niche product into the centerpiece of a multibillion-dollar wellness craze, driving booming supplement sales and spawning a new crop of protein-fortified foods that now saturate supermarket shelves and social media feeds.

Yet for all the industry’s growth and rebranding, one thing hasn’t changed: Protein powders still carry troubling levels of toxic heavy metals, according to a new Consumer Reports investigation. Our latest tests of 23 protein powders and ready-to-drink shakes from popular brands found that heavy metal contamination has become even more common among protein products, raising concerns that the risks are growing right alongside the industry itself.

For more than two-thirds of the products we analyzed, a single serving contained more lead than CR’s food safety experts say is safe to consume in a day—some by more than 10 times.

“It’s concerning that these results are even worse than the last time we tested,” said Tunde Akinleye, the CR food safety researcher who led the testing project. This time, in addition to the average level of lead being higher than what we found 15 years ago, there were also fewer products with undetectable amounts of it. The outliers also packed a heavier punch. Naked Nutrition’s Vegan Mass Gainer powder, the product with the highest lead levels, had nearly twice as much lead per serving as the worst product we analyzed in 2010.

We advise against daily use for most protein powders, since many have high levels of heavy metals and none are necessary to hit your protein goals.

Chemist and food safety researcher at Consumer Reports

Nearly all the plant-based products CR tested had elevated lead levels, but some were particularly concerning. Two had so much lead that CR’s experts caution against using them at all. A single serving of these protein powders contained between 1,200 and 1,600 percent of CR’s level of concern for lead, which is 0.5 micrograms per day. Two others had between 400 and 600 percent of that level per daily serving. CR experts recommend limiting these to once a week.

The lead levels in plant-based products were, on average, nine times the amount found in those made with dairy proteins like whey, and twice as great as beef-based ones. Dairy-based protein powders and shakes generally had the lowest amounts of lead, but half of the products we tested still had high enough levels of contamination that CR’s experts advise against daily use.

There’s no reason to panic if you’ve been using any of the products we tested, or if you take protein supplements generally. Many of these powders are fine to have occasionally, and even those with the highest lead levels are far below the concentration needed to cause immediate harm. That said, because most people don’t actually need protein supplements—nutrition experts say the average American already gets plenty—it makes sense to ask whether these products are worth the added exposure.

Consumers often assume supplements deliver health benefits without risks, says Pieter Cohen, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “But that’s not true.”

CR’s experts agree. “For many people, there’s more to lose than you’re gaining,” says Akinleye, who suggests that regular users of protein supplements consider reducing their consumption.

Unlike prescription and over-the-counter drugs, the Food and Drug Administration doesn’t review, approve, or test supplements like protein powders before they are sold. Federal regulations also don’t generally require supplement makers to prove their products are safe, and there are no federal limits for the amount of heavy metals they can contain.

What CR’s Tests Found

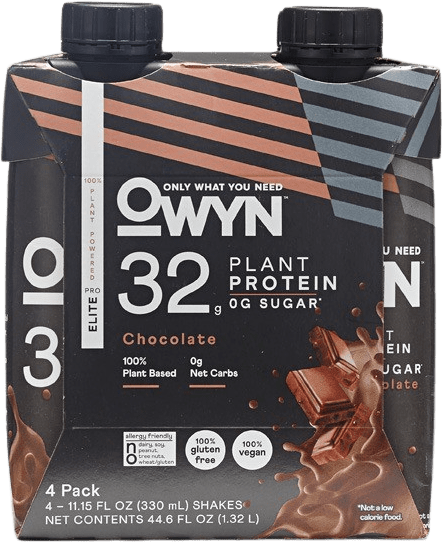

For our tests, CR selected a range of bestselling dairy-, beef-, and plant-based protein supplements, including chocolate- and vanilla-flavored protein powders and ready-to-drink protein shakes. We selected the flavor for each product tested based on popularity and availability at the time of purchase.

We purchased multiple samples of each product, including two to four distinct lots, over a three-month period beginning last November. CR bought the products anonymously from a variety of sources, including popular online retailers like Amazon and Walmart, and at supermarkets and health food stores in New York state, such as the Vitamin Shoppe and Whole Foods Market. Then CR tested samples from multiple lots of each product for total protein, arsenic, cadmium, lead, and other elements. Because the results are based on an average of these samples, which were collected over a specific period of time, they may not mirror current contaminant levels in every product. Even so, the findings highlight why consumers should carefully consider the role of protein powders and shakes in their diet. For more details on our testing methods and results, see our methodology sheet (PDF).

All products met or exceeded their label claim of protein in our tests, offering between 20 to 60 grams of protein per serving. Lead was the main heavy metal that emerged as an issue. About 70 percent of products we tested contained over 120 percent of CR’s level of concern for lead, which is 0.5 micrograms per day. Three products also exceeded our level of concern for cadmium and inorganic arsenic, toxic heavy metals that have been classified as a probable human carcinogen and known human carcinogen, respectively, by the Environmental Protection Agency.

When you fortify [your] diet with supplements, you’re putting yourself at greater risk.

Professor of health and kinesiology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

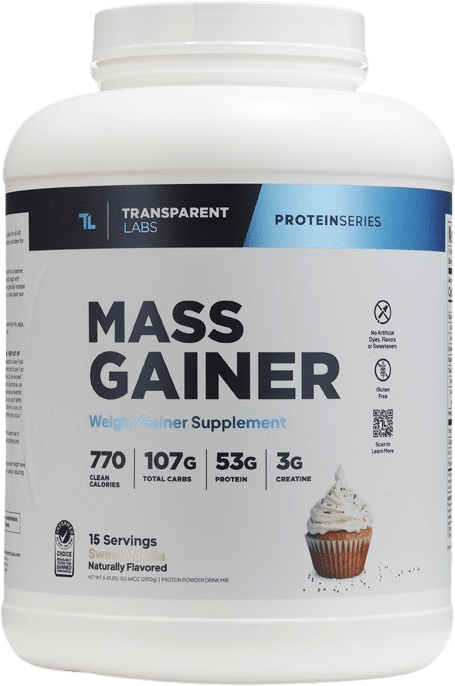

Two plant-based protein powders contained enough lead that our experts advise against consuming them. Naked Nutrition’s Mass Gainer powder contained 7.7 micrograms of lead per serving, which is roughly 1,570 percent of CR’s level of concern for the heavy metal. One serving of Huel’s Black Edition powder contained 6.3 micrograms of lead, or about 1,290 percent of CR’s daily lead limit.

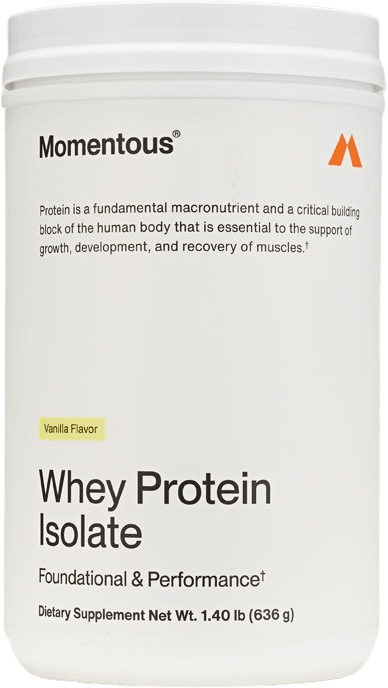

Two other powders contained lead between 400 and 600 percent of CR’s level of concern: Garden of Life’s Sport Organic Plant-Based Protein and Momentous’ 100% Plant Protein. Consumers should limit these to once a week, Akinleye says. (See company responses below.)

The only non-plant-based protein powder with lead detected at over 200 percent of CR’s level of concern was MuscleMeds’ Carnivor Mass powder. Six additional plant-based powders, five dairy-based powders and shakes, and one beef powder contained lead above CR’s level of concern.

We also found measurable levels of cadmium and inorganic arsenic in some products. One serving of Huel’s Black Edition plant-based protein powder contained 9.2 micrograms of cadmium, more than double the level that public health authorities and CR’s experts say may be harmful to have daily, which is 4.1 micrograms.

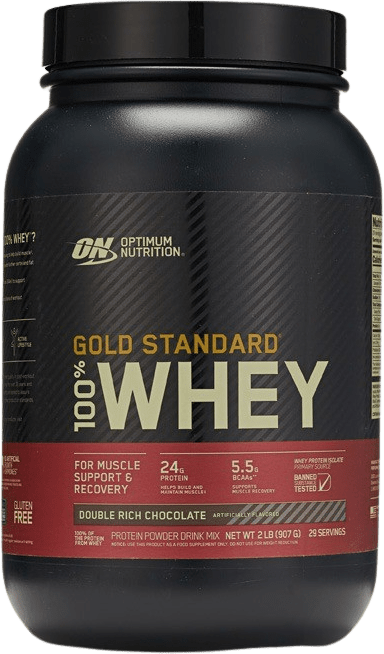

Another plant-based option, Vega’s Premium Sport powder, had enough cadmium that one serving would also put you just over that level. In one dairy-based product, Optimum Nutrition’s Serious Mass whey protein powder, we also detected 8.5 micrograms per serving of inorganic arsenic, which is twice the limit of what our scientists say is safe to consume daily.

Our tests also found no meaningful difference between the average detectable lead level of the vanilla-flavored products and the average detectable lead level of the chocolate-flavored products, though previous tests by CR and others have identified chocolate as a notable source of heavy metal contamination. The average concentration of lead in the chocolate- and vanilla-flavored products we tested was 17.3 parts per billion and 15.4 ppb, respectively.

(6 scoops)

(4 scoops)

(2 scoops)

(2 scoops)

(1 scoop)

(2.5 scoops)

(6 scoops)

1. Momentous told CR these products have been discontinued and are no longer commercially available. We included them in our results because protein supplements have a long shelf life and consumers may still have them in their pantries.

2. This recommendation is based on the 8.5 mcg of inorganic arsenic found in this product. This is the only product where another heavy metal posed a comparatively higher risk than lead.

3. Vega told CR the product has been renamed Vega Protein + Recovery and that the company had changed its pea sourcing to North America.

-

Under Prop 65 regulations for lead or other substances that are “known to the state of California” to cause birth

defects or other reproductive harm, products that exceed the MADL must carry a warning label.

Unlike Prop 65, which takes into consideration consumers’ average exposure over time and dietary frequency to calculate whether a product exceeds the MADL and requires a warning label, Consumer Reports assumes one serving a day of the product in its risk assessment calculations. This difference in methodology means no Prop 65 judgments can be made from CR’s findings. Our results are meant to provide guidance on which products have comparatively higher levels of lead, not to identify the point at which lead exposure will have measurable harmful health effects, or to assess compliance with California law. For more information, see our testing methodology sheet.

Protein Companies Respond

Prior to publication, CR contacted the manufacturers of all 23 products we tested and shared our results and methodology with them. Five companies have not responded to our requests for comment: BSN, Dymatize, Jocko Fuel, Muscle Milk, and Owyn. Optimum Nutrition declined to comment, and Huel did not respond to questions about the amount of cadmium found in its product. PlantFusion and Transparent Labs responded only after publication.

Of those that responded, many say that lead is a naturally occurring element that is difficult to avoid, particularly in plant-based products. Nine companies—Equip Foods, Garden of Life, KOS, Momentous, Muscle Meds, Muscle Tech, Orgain, Transparent Labs, and Vega—say they test both their ingredients and finished products for heavy metals.

A spokesperson for Huel says that its ingredients undergo “rigorous testing” and that the company is “confident in the current formulation and safety of the products, which is well within the levels set out by NSF.” The National Sanitation Foundation is a nonprofit public health organization that evaluates dietary supplements against specific standards set by the group, which are described below.

Naked Nutrition sources its ingredients from “select suppliers” that provide documentation attesting that they were checked for heavy metals, says James Clark, chief marketing officer. “We take our customers’ health very seriously,” he says, noting that Naked Nutrition has requested a third-party test of its Mass Gainer powder in response to CR’s findings.

John Koval, a spokesperson for Abbott, which makes Ensure, says that the lead levels CR found in its shakes are low for a product made with plant protein and that “consumers can be assured the product is safe.” A spokesperson for Quest says that the levels of lead CR detected in its products are “evidence that our robust food safety programs are working effectively.”

Maribel Aloria, Vega’s head of food science and regulatory, says the company “complies with all required safety standards and regulations” and that CR’s cadmium findings are “inconsistent” with the company’s regular testing results. She adds that the firm operates under California Proposition 65 consent decrees—legally binding settlement agreements that may allow companies to adhere to higher thresholds.

Such agreements are typically signed to resolve claims that a company violated a California law requiring that businesses warn consumers before exposing them to certain harmful chemicals. In total, Vega has paid about $336,000 in penalties to resolve allegations made in 2013 and 2018 that its products contained high levels of lead, cadmium, or other heavy metals without appropriate warning. As part of the settlements, Vega admitted no wrongdoing.

Earlier this year, Vega renamed the plant-based protein powder we analyzed and changed its sourcing practices for a key ingredient. The company now sources its pea protein—which is the first listed ingredient in the rebranded Vega Protein + Recovery—from North America instead of China. “Because naturally occurring heavy metal levels in plant proteins can reflect the soil in which crops are grown, this sourcing change is relevant to any testing considerations,” Aloria says.

Momentous also recently conducted a “massive overhaul” of its products to improve sourcing and “clean up formulas” for its dairy and plant-based protein powders, says spokesperson Will McClaran. “The Momentous products [CR] tested have been discontinued and are no longer commercially available,” McClaran says. (Discontinued products are marked with a footnote in the chart above. We included them in our results because protein supplements have a long shelf life and consumers may still have them in their pantries.)

Spokespeople for Garden of Life US and Orgain say their products are safe for daily use despite CR’s recommended limits. They also specified that the companies’ limits for heavy metals are determined by closely following the latest food safety guidance from the FDA, EPA, World Health Organization, and European Food Safety Authority.

Most of those organizations do not have limits or guidelines for heavy metals in protein powders or dietary supplements, particularly with regard to lead. The EPA does not regulate lead levels in food but has set an action level of 10 parts per billion for lead in tap water. (The concentration of lead we found in the Garden of Life and Orgain products was 61 and 15 ppb, respectively.) The FDA has not set any action levels for lead in protein powders or shakes. The WHO has published no guidance on lead in supplements and, through its joint committee with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, has said there is no level of lead that is safe to consume weekly. The maximum amount of lead permitted in food supplements according to the EFSA is 3,000 ppb (3 mg/kg), a level that CR’s food safety experts say is far too high to be health protective.

Momentous and Vega say their products are independently tested to ensure they meet standards set by the NSF. To obtain certification by the NSF, dietary supplements must adhere to the group’s limits of 10 micrograms per day for lead and inorganic arsenic, and 4.1 micrograms per day for cadmium.

Muscle Meds says it tests its products to ensure compliance with a similar lead limit, 10 micrograms per serving. Naked Nutrition says it is “in the process of obtaining” NSF certification.

We also shared our results with the FDA and asked about its oversight of the protein supplement industry. A spokesperson says the agency monitors contaminants in protein powders and shakes through its toxic element compliance program, special FDA surveys, and through a cooperative agreement with the states for laboratory funding.

“We will review the findings from Consumer Reports’ testing along with other data we have collected to better inform where to focus our testing efforts and enforcement activities,” the FDA spokesperson says.

Understanding Lead Exposure

It’s important to put CR’s daily exposure limits for heavy metals into context, says Goldman, the Cambridge Health Alliance physician. In the chart above, one of the ways results are shown is as a percentage of CR’s level of concern for lead in one serving of the protein powder or shake.

This level is based on the California Prop 65 maximum allowable dose level (MADL) for lead—0.5 micrograms per day—which has a wide safety margin built in. “We use this value because it is the most protective lead standard available,” says Sana Mujahid, PhD, who oversees food safety research and testing at CR. “There is no safe amount of lead, and we think your exposure to it in the food and water supply should be as low as possible.”

Jeff Ventura, vice president of communications for the dietary supplement trade group, Council for Responsible Nutrition, challenged CR’s level of concern for lead, saying it “creates a misleading impression of risk.” (Three of the products CR tested contained ingredients made by the trade group’s member companies.) “A finding that a product exceeds CR’s self-imposed threshold is not the same as exceeding a government safety limit, nor is it evidence of any safety risk to consumers,” Ventura says.

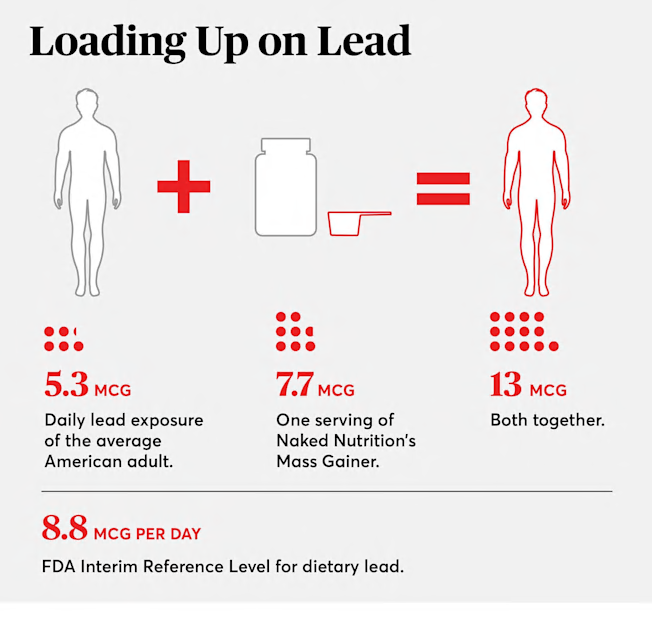

There are no broad federal guidelines setting dietary lead limits for the adult population. The FDA has set “interim reference levels”—these are estimates, not regulations or action levels, designed to protect against lead toxicity—for children and women of childbearing age. Those levels are currently 2.2 micrograms and 8.8 micrograms per day, respectively. An FDA spokesperson told CR there is sufficient evidence that the 8.8 micrograms per day benchmark should be applied to all adults.

The average American adult is exposed to up to 5.3 micrograms of lead each day through their diet, according to a 2019 analysis published by scientists at the FDA. For comparison, one serving of Naked Nutrition’s Mass Gainer contained 7.7 micrograms of lead, and a single serving of Huel’s Black Edition contained 6.3 micrograms. That means someone taking a single serving of one of these supplements daily is likely exceeding the FDA’s interim reference level for dietary lead.

Graphic: Consumer Reports Graphic: Consumer Reports

And food is not the only source of lead exposure. It can also be present in the air, soil, and household contaminants like dust or paint chips, pushing one’s daily exposure tally even higher.

Generally speaking, it’s a good idea to cut down on lead exposure when you can, says Goldman at Cambridge Health Alliance. Supplements in particular are often not worth the risk, especially if they haven’t been recommended by a doctor, she says. “Why take in unnecessary lead with protein powder?”

The Protein Problem

One of the main reasons people turn to supplements is the belief that their diet falls short on protein—a concern that many experts say is overblown. Americans need much less protein than they think, says Nicholas Burd, PhD, a professor of health and kinesiology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who has studied protein extensively. “I’m constantly trying to pull protein out of people’s diets.”

The average healthy adult needs roughly 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight (0.36 grams per pound), according to federal nutrition guidelines. For a 170-pound adult, that breaks down to about 61 grams of protein, which can be achieved by eating a cup of plain Greek yogurt and 3.5 ounces of chicken breast (or 5 ounces of tempeh).

That level is only a starting point, says Burd, who adds that experts advise certain groups, like pregnant people and specific types of athletes, to consume more. Older adults, for instance, should aim for about 1 to 1.3 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight (0.45 to 0.59 grams per pound) to offset the decline in muscle mass associated with aging.

Even so, studies have found that most people, even vegans, are capable of getting more than enough protein through their diet alone. The latest federal survey of U.S. eating habits found that Americans of all age groups exceed the recommended dietary allowances for protein (PDF), with men clocking in at over 155 percent of the recommendations and women at over 135 percent. But many people still worry they are deficient, Burd says.

Americans have been hooked on the idea of maximizing protein since the early 2000s, when a study suggested a connection between increased protein consumption and weight loss, says Hannah Cutting-Jones, PhD, a food historian and assistant professor at the University of Oregon in Eugene. But unlike other diet trends, protein mania has yet to wane.

In recent years, prominent health and fitness influencers like Peter Attia, MD, and Gabrielle Lyon, DO, have helped popularize the notion that the federal recommendations are woefully inadequate. In viral social media posts and during appearances on popular podcasts, they’ve argued that the amount of protein needed to promote overall muscle health is likely double—or more—what the guidelines suggest.

But those arguments aren’t supported by the latest research. A 2020 meta-analysis found that the intake levels set forth in the federal guidelines are enough to meet the needs of the average adult and that eating more had beneficial effects on lean mass only in very specific circumstances. (For instance, eating extra protein helped people who were restricting calories preserve more lean mass, but only when combined with resistance training.) Notably, it also found that among people neither dieting nor resistance training, chronically overconsuming protein had little effect.

Lyon said in a statement emailed to CR that the meta-analysis was flawed because the “high protein” groups studied were not eating enough protein and the median length of the 18 trials studied was only 12 weeks. “The overarching point I’ve helped popularize, that the current protein [Recommended Daily Allowance] is too low, comes down to the difference between avoiding deficiency and optimizing health,” Lyon said. Attia did not respond to a request for comment.

Regardless, Burd’s message hasn’t sunk in for most people. “I’m fighting a losing battle,” he says, adding that he frequently finds himself in arguments with laypeople about whether they’re getting enough protein. “I get so much pushback.”

We’ve created this health halo around protein. It gives us an excuse to eat a lot of things we shouldn’t be eating.

Food historian and assistant professor at the University of Oregon

Around 60 percent of Americans have actively tried to boost their protein intake in the past three years, CR’s nationally representative survey (PDF) of 2,153 U.S. adults found in August. About 1 in 4 said they reach for protein powders or shakes at least once a week, and 42 percent of Americans say they eat protein-fortified foods that often.

“I’m not the protein police . . . but when you fortify [your] diet with supplements you’re putting yourself at greater risk,” Burd says. Some supplements and fortified foods today contain more protein per serving than research has shown your body can use, which is about 25 to 30 grams per meal. What’s more, regularly overconsuming protein could also make your body more efficient at wasting it, effectively raising your baseline protein requirements without much benefit, Burd says.

Supermarkets today carry high-protein pastas, cereals, popcorn, and ice creams, along with protein-fortified sodas and waters. That’s just a slice of the more than 10 thousand products that have come to market with an added protein claim since 2010 in the U.S., according to market research firm Mintel.

“It’s nuts,” Cutting-Jones says. “Protein is in everything now.”

A recent study focusing on Special K cereals found that simply labeling a cereal as “high protein” was enough to make people believe it was healthier, even when it wasn’t. Participants rated Special K Protein as more nutritious than the original, despite it actually having more sugar, sodium, and calories per serving.

“We’ve created this health halo around protein,” Cutting-Jones says. “It gives us an excuse to eat a lot of things we shouldn’t be eating . . . things that have felt like they’re off limits because they’re packed with ingredients we don’t recognize.”

There’s no reason for the average person to turn to protein supplements or protein-fortified processed foods, Burd says. “You can 100 percent meet your protein demands by eating whole foods.”

How Heavy Metals Get Into Protein Powder

Although there were some exceptions, products made with plant-based proteins generally tested higher for lead than those using meat- or dairy-based sources. All the plant-based powders CR tested relied on pea protein as a main ingredient. Though soy remains among the most popular plant-based protein in terms of total crop volume, pea protein has emerged as a popular alternative due to its flavor profile and comparatively low allergenicity, says Priera Panescu Scott, PhD, a senior scientist at the Good Food Institute, a nonprofit focused on protein alternatives.

CR’s tests did not determine whether the pea protein itself was a noteworthy source of additional contamination, or if the difference between the groups was due to the natural tendency of all plants to take up lead.

Certain foods have unavoidable trace amounts of lead in them because of the environments where crops are grown and animals are raised. Heavy metal contamination can come from natural sources—because lead naturally exists in the earth’s crust—or from human activity like industrial pollution, wastewater irrigation, or road dust. Plants are particularly susceptible because they naturally absorb whatever nutrients or contaminants are in the soil, water, and air around them. For animal-based products like milk, the primary sources of heavy metal contamination in the cow’s environment include the feed, water, and soil, Akinleye says.

Extracting concentrated protein from plants is a complex, highly mechanized process. With every additional step, there’s a chance of introducing contaminants such as lead, says Goldman, the Cambridge Health Alliance physician who has studied lead exposure.

Lead could enter pea protein at the manufacturing plant, when the dried peas are dehulled and ground into flour, depending on the type of machines and metals used, says Goldman. It could also be introduced during the process where the flour is mixed with water to separate the protein from the starch and fiber, if the water wasn’t tested for contamination. The final step of the process, where the protein is coagulated with food-grade acid, neutralized, and spray-dried into the powder found in many foods and supplements, also offers opportunities for contamination, depending on the materials used.

Many companies don’t disclose where they source their pea protein, making it hard to know exactly where the products we tested came from. Historically, though, much of the pea protein used in U.S. food production is imported from China, according to data from the U.S. International Trade Commission. That’s notable because while the FDA has the authority to audit foreign supplement makers, it rarely does.

The Problem With Regulations

Protein powders and shakes, like all dietary supplements, fall into something of a regulatory gray area.

There is no federal limit specifying the amount of lead allowed in protein powders. And while the FDA requires that manufacturers keep their products free of harmful contaminants, it largely leaves it up to companies to decide what counts as harmful and test their own products for compliance.

Before 1994, manufacturers had to prove herbal products were safe before selling them. That changed after Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act. The law sharply limited the FDA’s authority, leaving supplements far less regulated than drugs.

Today, supplements are “presumed safe unless found otherwise,” says Cohen at Harvard Medical School, and most products face scrutiny only after reaching the market—meaning unsafe or contaminated supplements can reach consumers before problems are caught.

When these products that should be straightforward contain more heavy metals than expected, that exposes the challenge for consumers these days.

Associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School

Manufacturers generally don’t even have to notify the FDA when introducing a new product. A 2023 Government Accountability Office report found the FDA’s oversight of the supplement industry so lacking that it urged Congress to expand its authority. The report noted that the FDA relies largely on voluntarily submitted complaints and inspections to identify safety issues and ensure companies are complying with manufacturing guidelines.

Those inspections cover only a fraction of the industry. There are currently about 12,000 registered supplement manufacturers, according to an agency spokesperson. Last year the FDA inspected only 600 of them: 510 domestic and 90 foreign.

With so little oversight, people who turn to supplements out of concern for their health are left to navigate the risks on their own. “When these products that should be straightforward contain more heavy metals than expected, that exposes the challenge for consumers these days,” says Cohen.

Advice for Consumers

Limit exposure. If you are going to use protein supplements, you can reduce your lead exposure by limiting the number of servings you have each week and avoiding products with the highest amounts of lead in our tests, says Akinleye, the CR food safety researcher who oversaw this testing project. “We advise against daily use for most protein powders, since many have high levels of heavy metals and none are necessary to hit your protein goals.”

Avoid products with Prop 65 warnings on the label, and use CR’s chart above as a guide to seek out those with low levels of heavy metals. This is especially important for children and people who are pregnant or could become so.

Scrutinize your shakes. Before making a purchase, check to see if test results for the product are available online. But be warned: Few companies make their heavy metal testing results public. Of the brands we tested, only Momentous and Transparent Labs told us they publish them on their websites, and two additional companies—KOS and Equip Foods—say they will provide results to customers upon request. If test results are unavailable, consider opting for products that use dairy-based sources of protein rather than plant-based. Better yet, make your own shakes by swapping out the powders for high-protein foods like peanut butter or Greek yogurt.

Don’t succumb to protein mania. Most people don’t need supplements or protein-fortified foods to meet their protein goals. You can get a more individualized estimate of your protein needs by using the Department of Agriculture’s calculator, but the general guidelines are as follows: Most adults need 0.36 grams of protein per pound of body weight. For some people, like older adults, pregnant people, and serious athletes, it can be useful to shoot for more, but there are no official recommendations.

Choose whole foods over protein-fortified products. Avoid defaulting to the protein-added versions of everyday products, like bread and pasta. Instead, opt for whole foods that are naturally high in protein, like beans, lentils, tofu, eggs, dairy, fish, poultry, and lean meats, says Burd, the University of Illinois professor. “Protein mania is rampant,” he continued. “If you [have] a healthy eating pattern, there’s certainly no reason you need an isolated food protein.”

Editor’s Note: This article, originally published Oct. 14, 2025, has been updated to include company comments received after publication; to add details about the flavors tested; and to indicate that three manufacturer comments reference testing and certifications performed by the National Sanitation Foundation, not the National Science Foundation.