No, the CFPB Is Not Handing Out Cash to People Scammed on Zelle and Cash App (Despite What These Influencers Are Saying)

Social media stars are peddling misinformation and dubious financial advice, and undercutting the federal government's consumer complaint database

A new generation of social media influencers is using a surprising tool to peddle misinformation and dubious financial advice: the consumer complaint portal maintained by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), an embattled federal agency.

Two influencers in particular, Daraine Delevante and Gilbert Graim Jr., have built large social media audiences by offering online personal finance classes, e-books, and complaint templates while incorrectly claiming that anyone who submits a complaint to the CFPB will receive funds from agency settlements with the peer-to-peer payment platforms Zelle and Cash App.

In this July 2025 video, a social media influencer, Daraine Delevante, superimposes his own voice on an AI-generated avatar of himself as a toddler. He incorrectly tells his followers to file complaints with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to have medical debt removed from their credit reports.

CR asked experts at the nonprofit National Consumer Law Center to examine the advice and materials produced by Graim and Delevante. Diane Thompson, NCLC’s deputy director and a top CFPB official during the Biden administration, said they are egregious examples of false “pseudo-legal advice.” She added that anyone who bought their financial products or followed their advice “should consider filing complaints with the CFPB, the Federal Trade Commission, and their state attorney general.”

The CFPB did not respond to a request for comment, and the FTC declined to comment.

In an interview, Delevante said Cash App and Zelle were unfairly targeting him to divert attention away from their own shortcomings in combating online fraud and scams. “Shouldn’t they be working to help out people who have lost money on their platforms? They shouldn’t be coming after the messenger,” he said.

After this article was published, Graim wrote in a statement that Consumer Reports had taken his words “completely out of context” and that while some people “may have interpreted my video as encouraging fraudulent claims,” he would never encourage them to lie.

“While my tone was somewhat joking, I was serious that whether people believed this happened to them or not, they should put in a claim and allow an investigation to determine if anything happened that violated consumer laws,” Graim wrote. He added that he does not sell any product or endorse the sale of any product that would lead to the filing of consumer complaints, and that while he shares complaint templates with his followers, he does not directly sell them.

What Is the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Why Does It Matter?

Here’s what the agency has been doing for U.S. consumers since it was created and what could change.

A Spike in CFPB Complaints About Zelle and Cash App

A rash of influencer-driven complaints came to light as part of a recent CR analysis of the CFPB complaint database.

In the first eight months of 2025, more than 61,000 complaints were filed against Zelle and Cash App, nearly 15 times the volume of complaints made against them in any previous full-year period since the agency began accepting complaints about those companies. When CR brought this to their attention, Zelle and Cash App presented evidence that a vast majority of the complaints appear to have originated with videos and products endorsed and sold by Delevante and Graim.

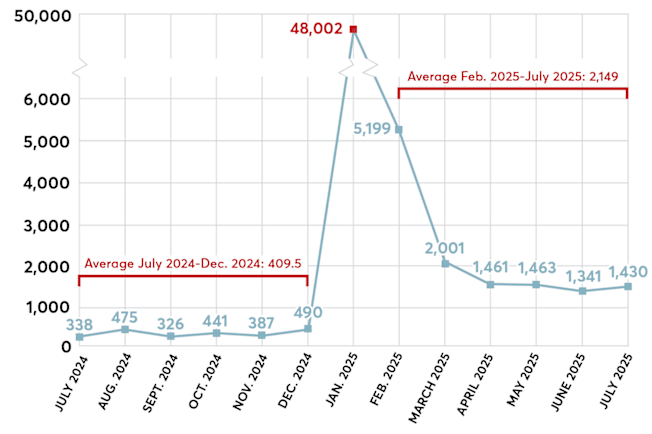

Complaints Received by the CFPB, by Date

Complaints about Zelle and Cash App increased nearly 15-fold in early 2025 after two social media influencers told followers to file complaints with the agency. Since then, the rate of complaints about the two payment apps is still more than four times what it was in late 2024.

Indeed, many of the complaints contain language that is nearly identical to what these influencers advised their followers to submit. In January and February, for example, Graim incorrectly told millions of TikTok users that Zelle and Cash App would soon be handing out reimbursement checks to anyone willing to submit a formal complaint.

Delevante, meanwhile, uses Instagram, YouTube, and other social media platforms to hawk a wide range of financial products, including a $77 complaint template in the form of a downloadable Microsoft Word document. CR purchased one, which reads, in part: “Like many other consumers, I have been negatively impacted by Zelle’s lack of security measures and by my bank’s failure to resolve unauthorized transactions and provide reimbursements.”

But both influencers are offering incorrect advice related to genuine CFPB allegations.

In January, the agency ordered Block, which operates Cash App, to pay $175 million to compensate consumers who lost money to scams while using the app. It said Cash App put users at risk by using weak security protocols, failed to fulfill its legal obligation to investigate and resolve disputes about unauthorized transactions, and used deceptive tactics to prevent users from seeking help.

Consumers who lost money to scams while using the app may be eligible to collect money from the settlement funds. But exactly who qualifies for compensation, and how much they can get, has nothing to do with the CFPB’s complaint portal. Rather, the government’s consent order required Cash App and Block to find, contact, and reimburse customers who have been scammed. (Scam victims can find some details, including contact information, at this Cash App site.)

A spokesperson for Cash App said it takes “customer complaints seriously” and has “made significant improvements to how we identify and act on customer complaints.” Cash App estimates that fewer than 1 out of 10,000 transactions on its app results in a confirmed scam. “We’ve invested in better tools and processes to track complaints, spot trends, and understand what customers are experiencing—whether it’s a one-time issue or something more widespread,” Cash App said.

Separately, in December, the CFPB filed a lawsuit against Early Warning Services (which operates Zelle) and three of the largest banks in the U.S. (Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo), which co-own the platform, accusing them, too, of failing to adequately protect customers from “widespread fraud.” In its lawsuit, the CFPB said that hundreds of thousands of Zelle customers had filed fraud complaints with the company and had been almost universally denied help or refunds, and that “some were even told to contact the fraudsters directly to recover their money.”

The agency said customers at those banks lost an estimated $870 million due to fraud and scams over seven years ending in 2024, and the CFPB sought refunds for customers and civil penalties from Zelle. But in March, that lawsuit was dropped without explanation. This month, the New York Attorney General’s Office sued Zelle, reiterating many of the allegations from the dismissed CFPB lawsuit and putting the amount lost to fraud and scams at more than $1 billion.

In a statement, Zelle pointed to both Graim and Delevante, saying that “consumers were duped through social media into filing complaints based on a fabricated settlement.” A Zelle spokesperson added, “The real threat isn’t the payment method. It’s the criminals exploiting Americans through texts, DMs, and online marketplace scams.”

Thompson of the National Consumer Law Center says that, in fact, the spike in the database reflects many legitimate complaints about the prevalence of online fraud on peer-to-peer payments apps and the apps’ relatively high rate of denying refunds for customers when they lose money to a scam. “If we had pre-February 2025 CFPB in place, the CFPB would have welcomed the complaints and pushed for more substantive responses from Zelle and Cash App. The CFPB would not have been satisfied with their pro forma denials,” she says.

Just 15 customers of the more than 61,000 who complained about Zelle and Cash App have received a refund directly from the companies as a result of their complaint through the government portal, according to CFPB data. In almost every other case, the companies responded with a denial.

Both Zelle and Cash App say they’ve taken steps to reduce the amount of fraud and scams occurring on their platforms.

Cash App touts a new artificial intelligence model it uses to flag suspicious transactions and warn customers before they send money to someone. The company reported at the end of 2024 that its new scam detection program had helped more than 50,000 customers with more than $5 million in refunds.

Zelle says it requires all participating banks and credit unions to fully reimburse customers in instances of “confirmed fraud” and “eligible imposter scams.” Such a policy would be more robust than what’s required by federal law, but the company did not respond to a request to provide data on how much money had been returned to customers as a result. A 2024 Senate subcommittee analysis of the three top-transacting banks on Zelle—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo—found that the percentage of customers defrauded on the platform who received refunds declined from 62 to 38 between 2021 and 2023. Customers of those banks lost roughly $100 million to scams on Zelle during that time, the subcommittee found.

In this January 2025 video, social media influencer Gilbert Graim Jr. urges his followers to file complaints against the payments app Zelle—even if they've never lost money on the platform due to a scam. The video has led, in part, to a near 15-fold increase in complaints to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Graim has worked as a property manager for apartment complexes and currently serves as a member of the Planning and Zoning Commission in DeSoto, a Dallas suburb where he ran unsuccessfully for city council in 2023. In 2015, he was indicted by a federal grand jury on a drug trafficking charge that was later dropped. This year, he pointed to his political aspirations in seeking to expunge the charges from his record, but a federal judge denied his request.

On his website, Graim says that he started his company, Graim Solutions, to “level the playing field” and “provide a robust negotiating tool kit, ensuring no one is disadvantaged due to a lack of knowledge or resources.” The company was registered in Texas but is now listed as inactive after having failed to comply with tax requirements, state records show.

One of Graim’s January TikTok videos racked up 5.5 million views, and his videos about Zelle and Cash App have more than 10 million views combined. In the video, he said that anyone who filed a complaint against Zelle through the CFPB portal would get money regardless of whether they actually lost money to an online scam. (The video was removed from the platform after the publication of this article.) And in February, Graim incorrectly told his followers that “only people who put in a complaint with the CFPB” would be entitled to money back from Cash App.

Graim said in a statement to CR that the CFPB was an “investigative site,” and that “encouraging people to file complaints about services they use should not and is not a crime.”

Delevante, 35, represents himself as an expert in consumer law and runs a website called Consumer Law Secrets, but he is not an attorney. He refers to himself as “The Credit Hero,” and frequently posts videos on Instagram in which he offers financial advice to his followers. In some of those videos, his voice is superimposed on an artificial intelligence-generated toddler wearing a tuxedo (as in the video above).

Delevante did briefly speak with CR but declined to answer many of our questions. He says he immigrated to the U.S. from Jamaica as a teenager before serving in the U.S. Army. (Army National Guard promotional materials from 2020 list Delevante as a sergeant in the 42nd Infantry Division in New York.) He started the business out of his home in the Bronx in 2021 but registered it in Wyoming, a state known for its corporate privacy laws, and trademarked the phrase “Consumer Law Secrets” with the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 2023.

The website says Delevante started the company to “empower consumers burdened by generational misinformation,” but a disclaimer on his website makes clear that he is not a qualified attorney, accountant, or financial adviser, and that his products are for “educational and informational purposes only.” “My strategies and case studies are only estimates of what is possible,” it reads. “There is no assurance you’ll do as well or even close to as well as I have done or other clients. Results are based on many factors including luck, hard work, effort and years of hard work.”

Delevante’s business registration in Wyoming, like Graim’s in Texas, is also inactive, having missed a required tax filing, according to state records.

Delevante has faced questions about the accuracy and promised results of his financial advice and online products before. FTC records obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request show that at least four consumers filed formal complaints against him since 2022. In one, a Georgia consumer says he paid $1,000 for Delevante’s “system and coaching,” saw his credit score plummet when he used the advice, and got no response when he asked for a refund. “The guy is portraying himself to be a legal expert,” the complaint reads. “He is scamming lots of people who are struggling with debt and credit and taking advantage of them.”

Graim and Delevante are both part of a larger and worrisome trend, consumer advocates say, of social media-savvy content creators targeting especially vulnerable people who are seeking financial information in a chaotic digital marketplace. Their content often mixes practical, legitimate advice (“Baby, you send to the wrong person,” Graim says in one TikTok video, and your money “is gone.”) with pure misinformation and falsehoods (“Whether it happened to you or not, go put in a claim because they going to have to run you that check,” he says in the same video, as shown above).

Of course, Cash App and Zelle are not the first companies to be targeted by social media-led campaigns regarding consumer issues. In 2016, Wells Fargo was fined $185 million by the CFPB after bank employees illegally opened customer accounts without their approval and charged customers unjustified fees to meet sales quotas. The scandal became a sensation online and Wells Fargo faced an ensuing barrage of CFPB complaints.

The regulatory environment is different today. The CFPB has stopped pursuing much of its legal enforcement work, and the agency’s acting leaders have ended efforts to police digital payment companies. Last year, the CFPB finalized a new rule that would have allowed the agency to monitor and supervise apps like Cash App and Zelle. But the Republican-controlled Congress, at the behest of the current administration, reversed that rule in April.

Source: Consumer Law Secrets Source: Consumer Law Secrets

How You Can Protect Yourself Before and After an Online Scam

With fewer regulators policing financial companies, the result could be an even more confusing online marketplace in which it’s increasingly difficult for consumers to discern fact from fiction.

“It may get worse before it gets better,” warns Ruth Susswein, director of consumer protection at the nonprofit Consumer Action and a longtime proponent of the CFPB’s complaint portal. “We have to rely on our wits a bit more, be a little more suspect when we’re operating online, take a moment to consider if it sounds too good to be true, and turn to our elected officials to insist they provide some genuine help if they plan to stay in office.” Here are some practical tips.

Slow down and be alert. Scammers prey on the financially vulnerable and can exploit your fear about losing money or access to a bank account. If someone claiming to represent your bank or government agency contacts you, don’t assume caller ID is showing you the correct information. To put you off guard, scammers will often say that a matter needs to be handled immediately or your money could be at risk.

A few tried-and-true reminders when making any online purchase: Never give your financial info to anyone. Legitimate bank employees should never ask for your username, PINs, one-time access codes, or passwords. Don’t send digital app payments to strangers or sellers on social platforms.

Be skeptical of too-good-to-be-true claims. Social media scams tend to play on our emotions and use promises about big savings, discounts, and refunds to attract consumer attention. Be especially wary when such claims suggest you can get a payout even if you weren’t a fraud victim, as in these cases.

If you’re the victim of a payment scam, contact the bank or payment platform right away to let it know. While digital payments apps usually do not provide refunds for “induced” or “authorized” fraud—scams where a consumer is tricked into authorizing a payment—your report could help to catch the criminals and protect other users. And some payment apps do provide limited reimbursement for specific types of imposter scams, such as when the scammer gains access to your bank accounts without your knowledge or consent.

Report the scam to the Federal Trade Commission, the FBI, or your state attorney general’s office. The independent FTC, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), and state attorneys general investigate online fraud and potential violations of consumer protection laws, and take action against businesses or scammers engaging in illegal activities. Experts say that unless and until the CFPB’s regulatory authority is restored, fraud victims are better off reporting the incidents to the FTC or the FBI. Go to the FTC’s complaint portal or the FBI’s IC3 complaint portal.

When submitting a complaint to regulators or law enforcement officials, include specifics and documentation. The most effective consumer complaints include a detailed narrative of what happened, including how much money was lost, and as much supporting material as you can gather, including emails, screen shots of text and social media come-ons, invoices, and bank statements, says Charlotte Haendler, an assistant professor of finance at Southern Methodist University in University Park, Texas, who co-authored a working paper on what factors helped submitted CFPB complaints result in a refund.

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to reflect comments received from Gilbert Graim Jr. after publication.