Then & Now: Consumer

Champions For 80 Years

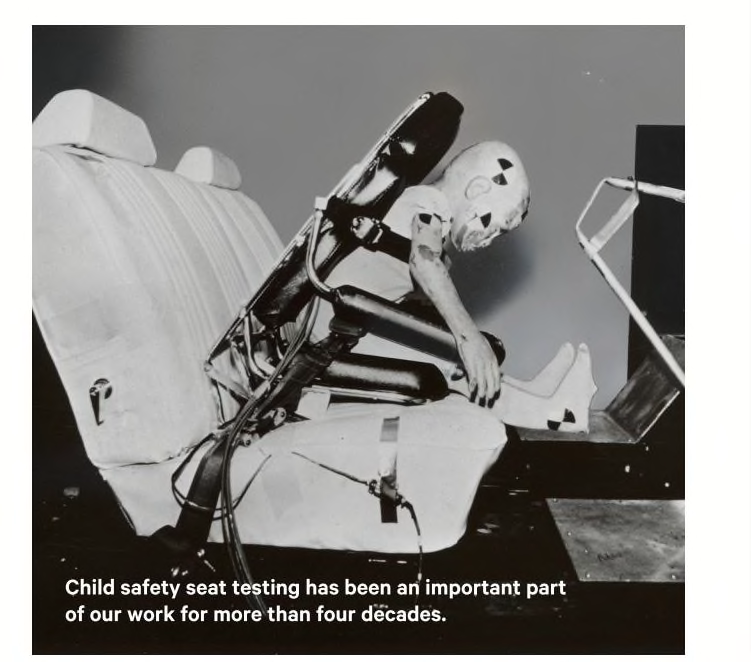

Child safety seats

THEN

When Consumer Reports first crash-tested child safety seats in 1972 to assess what would happen to a small child in a head-on collision, 12 out of 15 products were rated Not Accept- able. The day after CR released its 1974 report, the government proposed a stronger child-restraint standard. Starting in January 1981, manufacturers of child safety seats had to certify that their products would pass a rigorous crash test—very similar to the one Consumer Reports used and had proposed to the government.

NOW

Safety seats are among the most important products par- ents buy, which is why we test 40 of them per year. We recently spent two and a half years developing our own test protocol for crash-testing child seats to determine which ones provide an additional margin of safety beyond the basic federal standard. In the test, we incorporated real-world vehicle conditions including updating the seat bench, adding a front seatback, and increasing the speed of the simulated crash. While crash protection is key, our experts also do more than 1,000 installations a year to evaluate fit to vehicle and ease of use in a variety of vehicles at our 327-acre auto test track.

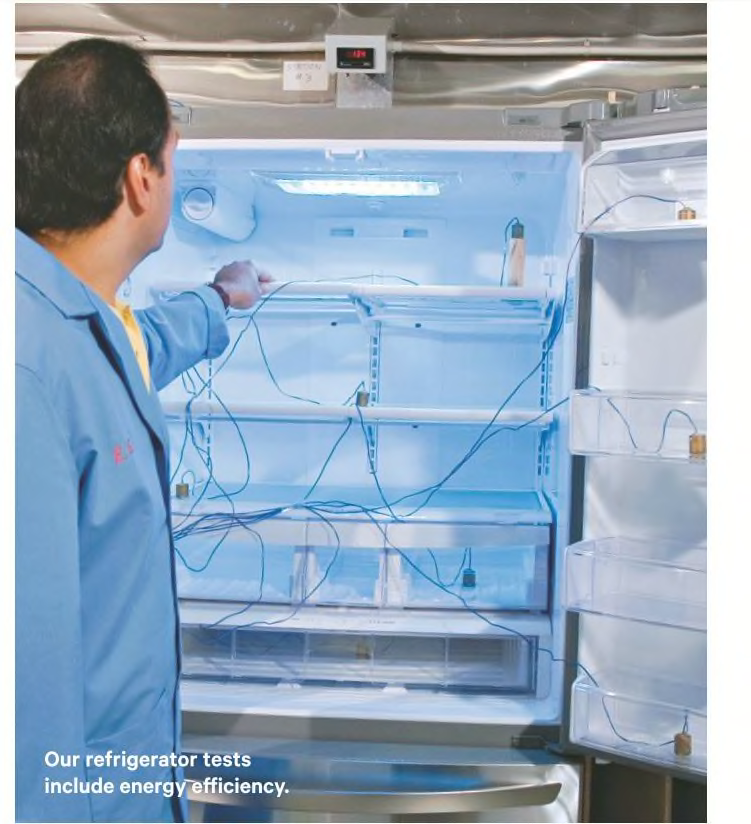

Application efficiency

THEN

In 1975, Congress ordered the Department of Energy to set mandatory standards for energy use by major household appliances. But the DOE refused, saying standards wouldn't be economically justified or result in "significant" energy savings. It took 10 more years, and a lawsuit from Consumer Reports and others, before a federal court decision in 1985 that said, just do it.

NOW

More than 30 years later, evolving energy standards have brought significantly more-efficient washers, dishwashers, air conditioners, and refrigerators. For example, the Department of Energy estimates a typical new refrigerator uses one-third the energy of a 1973 model, despite offering more storage space. All of the appliances we test comply with energy efficiency regulations; the energy consumption is listed on the yellow "Energy Guide" label on the product. Many models go further and comply with voluntary Energy Star labeling standards, which generally tell shoppers that those products are a designated amount more efficient than other models in that category. Our testers and advocates continue to work with government regulators to ensure products deliver an acceptable level of performance for consumers while delivering energy savings.

Cell phone number portability

THEN

Once upon a time, when cell-phone users switched to a new carrier, they forfeited their number. It was such a hassle that people tended to stick with a carrier, despite lousy service. Through our "Escape Cell Hell" campaign in the 1990s, consumers sent more than 22,000 letters to Congress urging lawmakers to pass number portability. That convenience became a reality in 2003.

NOW

A new cell hell (and landline hell) has popped up in recent years: The Federal Trade Commission received more than 3.5 million complaints in 2015 about unwanted phone calls. Robo-calls can compromise privacy, lead to millions in financial losses, and force consumers to incur fees and charges for unwanted texts and calls. In a big win for consumers, the Federal Communications Commission heard the concerns, including from the 50,000 petition signatures we sent, and voted to allow telephone carriers to offer effective robocall-blocking technology to their customers.

Consumers also won when Time Warner Cable took the lead among major companies in offering the free call-blocking service Nomorobo directly to its six million voice customers. We are using our online petition, which has garnered more than 600,000 signatures, to pressure other major companies to offer free robocall-blocking tools.

Chicken testing

THEN

Our 1978 tests found that up to half the chicken samples were contaminated with human or animal fecal matter, and many tested positive for E. coli and salmonella. Our tests through the years also found campylobacter, a bacteria that can cause diarrhea, nausea, and fever. We lobbied the government for limits on that bacteria; they were finally set in 2010.

NOW

This story doesn't have a happy ending—yet. Each year 48 million Americans are sickened by foodborne illness. In 2012 we launched the Consumer Reports Food Safety and Sustainability Center to address a number of the root issues plaguing our food system. The Center's work includes food-safety tests; one recent investigation found that almost all of the 316 raw chicken breasts we tested contained some type of potentially harmful bacteria. Tests on 458 pounds of ground beef found bacteria on every sample. We're working with government agencies to improve the food system, including increasing inspections and cracking down on misleading labels like "natural" that don't meet consumer expectations.

If Looks Could Chill

We know we're a little weird. (But hey, that's what makes us unique.) Here's more evidence: We're building a room that we can crank up to 120 degrees F. just so we can cool it down with air conditioners.

We moved into our headquarters in Yonkers, N.Y. in 1991. A couple of decades later, as products changed and technology advanced, the air conditioner lab wasn't as efficient as we needed it to be. In order to test rapidly and evaluate new product features effectively, we knew it was time for a rebuild.

We rate several dozen air conditioners a year. Our rigorous tests evaluate how quickly each model can cool a room down, how well it maintains that temperature, and how evenly it distributes the cool air. But setting up the units was taking too long; we wanted to focus more on the actual tests, so we looked for ways to streamline the process.

Inside and outside

The new AC test room is both simpler and more complex than the old one. It's the size of a room in your house. Actually, like several rooms, since one wall is adjustable to give each AC the appropriate challenge based on its output. Moving the wall used to require several technicians, a ladder, and more than an hour. Now, we've put the wall on tracks, and going from bedroom-size to living room-size takes one tester just seconds.

The room sits inside a larger chamber that acts as the uncooled part of the house. A second chamber replicates the outdoors. In both, we boost the heat and humidity. The old mock window was awkward, and the tape we used to seal it turned into a sticky mess in the heat and humidity, so in came a real double-hung window.

Reuse, recycle, rebuild

Any construction job can be a jolt to the bank account, and meeting complex technical requirements adds to the cost. As a nonprofit, we're always careful with our budgets, and this lab was no exception. (Subscriptions cover some of our costs; we rely on generous donors for the rest.)

The main savings came from tapping the expertise of our own staff, particularly project leader and mechanical engineer Chris Regan, who oversaw the construction. We pulled out miles of wire, reusing as much of that and other materials as we could, and saving thousands of dollars. And we installed LED lights, which are both energy efficient and cool, so they don't alter the temperature of the room.

More than half of the 200 old temperature and humidity sensors collected data we no longer use, so we pared them down to the essential 80. Those take readings twice a second and quickly and accurately transfer the data to new software.

Our product-testing division and advocates work together to push for strong energy efficiency standards, to save consumers resources and money. Most of the models we test are Energy Star rated, which should mean that they are measurably more efficient. But window ACs with that label have to be just 15 percent more efficient than conventional models. The efficiency premium for other appliances is greater: 20 percent for clothes dryers, for example, and 25 percent for washing machines. We're working with the EPA to set tougher standards for air conditioners.