Tracking Everyone With Coronavirus Is a Huge Task. These Systems Could Help.

- Public health officials are rushing to set up contact tracing to monitor everyone who may have been infected.

- Health workers will need to monitor the health of thousands, or millions, of patients as part of that task.

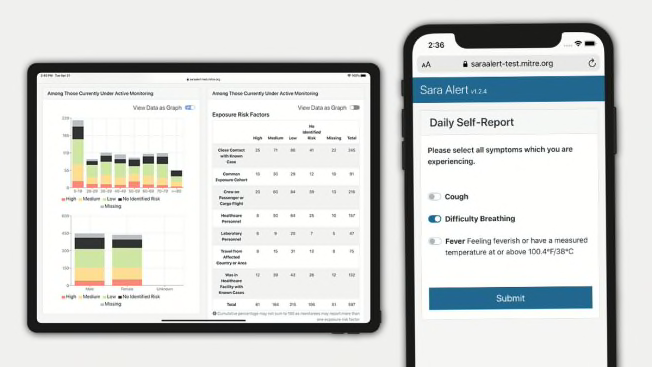

- Sara Alert and CommCare, two software systems, could help by automatically collecting data on symptoms.

Your phone buzzes with a notification: Do you have a fever or a cough? Is it hard to breathe?

Some people who have signed up for pilot programs in San Francisco; Danbury, Conn.; and throughout Arkansas have recently started getting automated messages like these every day, and more of us may soon join them. The questions—which can appear in a text message, an email, or an automated phone call—are designed to help public health officials monitor people known to be at risk of contracting COVID-19 and those who already have it.

They’re coming from state and local health departments that are testing two new messaging systems in a race to collect the data they need to slow the spread of the pandemic.

Last week, San Francisco began using CommCare, a system developed by Boston-area software company Dimagi, to automatically ask patients about their symptoms. And on Monday, Arkansas deployed a similar system called Sara Alert, from Mitre, a research nonprofit funded by the federal government.

These trials may provide a glimpse at the coming new normal in the U.S., as the country tries to rein in the pandemic and restart the economy without causing massive new waves of infection.

manuf manuf

Several states are already allowing some businesses to reopen, and others will eventually follow. But once we all start to mix and mingle again, public health experts say people will need to be monitored at extraordinary levels for a long while—possibly years—to keep the coronavirus in check.

To do that effectively, experts say the country needs a massive commitment to contact tracing—a vital, longstanding tool for keeping pandemics in check.

Here’s how contact tracing typically works: Investigators ask anyone who tests positive for COVID-19 about the places they’ve gone and the people they’ve seen in the previous two weeks, when they were likely to be contagious. Then, the investigators try to get in touch with every person the patient may have come into contact with, advising those people to self-isolate and monitor themselves for disease symptoms.

Putting the Pieces Together

Case management is just one of the two halves of contact tracing (PDF). The other is proximity tracking.

Proximity tracking can be conducted through traditional interviews or with technology like the program recently announced by Apple and Google. That system, which is supposed to start rolling out in May, would let you have your smartphone keep a temporary record of every other phone you linger near for a certain period of time.

If you eventually test positive for COVID-19, you can choose to hit a button that automatically notifies every other participant who came near you in the previous two weeks. And you’d get notified if you’d been near someone else who told the system about their own diagnosis.

This is where case management tools such as Sara Alert and CommCare can jump in to monitor people who may be infected.

The two kinds of contact tracing technology could talk to each other. Mitre and Dimagi are in discussions with Apple and Google about what it would take to integrate their software with the tech giants’ proximity tracing. In that scenario, people who are notified via the Apple-Google system that they may have been exposed to the virus would be given the option to sign up for Sara Alert or CommCare.

“If we relax social distancing, we’re going to have a rebound,” says Paul Jarris, Mitre’s chief medical advisor for health transformation and a former Vermont health commissioner. “We’ll need to quickly identify that [rebound], isolate people with symptoms, take their contacts and actively manage them on a daily basis. If there’s going to be a second wave, like the CDC says, we need to have a tool in place.”

CDC Director Robert Redfield told the Washington Post on Tuesday that a potential second spike of COVID-19 cases this winter could coincide with flu season, making it even more deadly than the current crisis.

Other Challenges Remain

Even as contact-tracing technology gains momentum across the country, several hurdles need to be overcome. The most fundamental problem is that COVID-19 testing is still extremely limited in the U.S. Without enough tests, contact tracing is far less powerful because it’s difficult to know who’s infected.

A second challenge is that any system would need to be widely adopted to be useful. Convincing the public to participate could require answering some difficult questions, like where sensitive health data is stored and how it might be reused later.

When it comes to privacy, how long agencies retain records and who can access them are critical questions, says Matthew Guariglia, a policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. His organization is devoted to bolstering privacy protections for consumers, and is often skeptical of new kinds of data collection. But, Guariglia says, “of all the COVID-related scenarios I’ve seen this one is the least likely to make me lose sleep.”

Mitre and Dimagi say their systems emphasize consumer privacy and data security: Mitre sends people’s health status updates to a centralized database maintained by the Association of Public Health Laboratories, which already runs sensitive systems for labs across the country. Dimagi manages health data in its own database, and both companies say they don’t make money by using the data for marketing or any other purpose. In both cases, the information that public health departments upload remains the departments’ property.

Public health agencies have long been custodians of private health information, and they have a good track record of protecting it and using it appropriately, says Dena Mendelsohn, director of health policy and data governance at Elektra Labs, a health technology startup, and a former CR senior policy counsel. “I don’t think we should have any more concern now than we did when public health agencies engaged in contact tracing in the past,” using old-fashioned tools, Mendelsohn tells CR.

The public health departments of San Francisco and Arkansas did not respond to questions about whether the data they are gathering for contact tracing could be reused for other purposes, such as research or law enforcement.

A final, near-term hitch is that public health departments are stretched so thin trying to contain the virus that they might not have the time, money, or staffing to evaluate and set up new systems, says Lori Freeman, CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials. “Introducing anything new to them at this point is really a crapshoot because they don’t have a lot of resources.”

Here, Sara Alert may have a head start. Since January, Mitre has been getting constant feedback from health departments about how they would use the system, and taking steps to make it easier and more useful. Arkansas, for example, asked for the system to be able to monitor current COVID-19 patients in addition to people who may have been infected—and Mitre promptly added that capability, Dillaha says.

CommCare isn’t being rolled out as broadly in the U.S. yet, but the company is well established in global health, and Dimagi says it has seen a lot of interest from public health officials.

Sara Alert and CommCare appear to be front-runners in the race to help health officials ramp up contact tracing with technology. Soon enough, you may be asked to enroll in one of them if it turns out you had a brush with a person infected with COVID-19—or if you test positive. In the coming months or years, the two contact tracing systems could become household names.

“For the foreseeable future, this is the new normal,” says Mitre’s Jarris. “This is part of our new experience.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated Paul Jarris's title. He is Mitre's chief medical advisor for health transformation, not its chief medical officer. It was originally published on April 23, 2020.