‘These Aren’t Statistics. These Are Babies.’ Why Online Misinformation About Infant Sleep Is More Dangerous Than Ever.

Cuts to federal funding for safe sleep education, combined with unsafe imagery flooding tired parents’ feeds and screens, are putting America’s babies at risk.

Two photos of adorable newborn babies appear side by side on a screen. Both babies are wrapped in a swaddle, and both are peacefully asleep. In photo A, the baby is nestled inside a cushioned lounger, which rests atop what looks like a bed mattress. In photo B, the baby is shown sleeping in a flat bassinet with nothing else—no cushions, no blankets, no extra padding.

“Okay, which one of these would be wrong, which one of these could we not use?” asked Dani Morin, the host of the Baby Safety Alliance’s online workshop for “mom influencers”—parents who want to make money from baby product companies by promoting their gear on social media.

Source: Baby Safety Alliance Source: Baby Safety Alliance

The workshop attendees typed their guesses into the chat, and Morin revealed the answer: Photo A is no good, and if you post something that looks like that on your feed, no company is going to be able to pay you for it. Infant loungers aren’t safe to use for sleep, she said, and shouldn’t be used in a bed. Photo B, however, could be part of a brand partnership, she said—an arrangement where a company pays an influencer for their social media content or videos, or sends them free stuff to review.

Morin knows all about what brands want from mom influencers: As a social media content creator herself, she has over 84,000 followers on Instagram and 739,000 on TikTok. She advocates in her videos for the “ABCs” of safe sleep, a simplification of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines: Babies should sleep Alone, on their Backs, in a firm, flat Crib or bassinet, to help prevent suffocation and lower the risk of sleep-related deaths.

Source: Instagram, TikTok Source: Instagram, TikTok

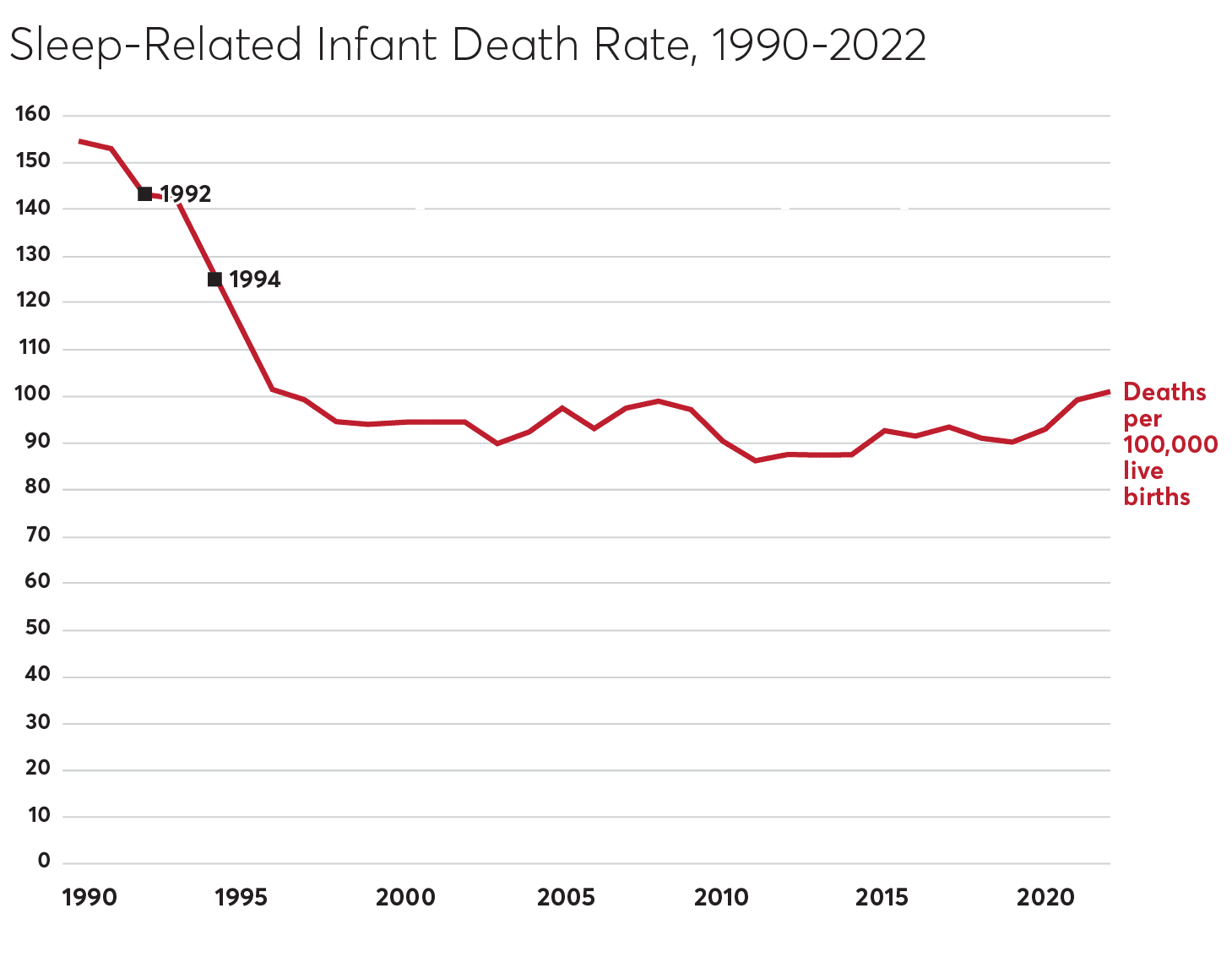

In 2022, approximately 3,700 babies died in their sleep. To put that into perspective, that’s 10 babies under 1 year old in America dying every day.

Researchers are still exploring possible theories as to why sleep-related deaths have risen in recent years.

Some say the onslaught of unsafe sleep imagery and messaging online and on social media could be to blame. The uptick loosely coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic, which not only increased people’s social media and internet use in general but also reduced contact between new parents and their physicians, and isolated people from their extended families and friends. New families may have had fewer reminders from trusted experts about the importance of safe sleep methods and less help with their babies overall. Studies have proven the not-so-surprising hypothesis that the more exhausted parents are, the less likely they are to consistently follow the ABCs of safe sleep.

Whatever the reason, researchers agree that this is a particularly dangerous time to weaken public awareness about how to keep babies safe.

“It took so long for people to understand that putting a baby to sleep the way maybe your grandparents did is not the right way, and I feel like there was a lot of momentum a decade or so ago about Back to Sleep, but now misinformation is something that we’re seeing in medicine quite a bit,” says Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at UC San Diego School of Medicine. She adds that, at a time when a person’s online follower count seems to confer expertise, “it’s nice to be able to fact-check opinions with actual data.”

But what happens when the programs that generate that data are eliminated?

What Happened to the Safe to Sleep Campaign?

At 5 a.m. Tuesday, April 1, 2025, the nine staffers of the Office of Communications of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) were all emailed reduction-in-force (RIF) notices. The entire office was eliminated, and with it, the Safe to Sleep public health messaging campaign to reduce SIDS and sleep-related infant deaths. Its contracts were all canceled, too. Its website is still live, but it isn’t being updated. Its free-to-order educational materials are, the fired staffers assume, just sitting in a warehouse somewhere, unused.

“The Safe to Sleep campaign is mission critical for our institute, and the idea that no one was going to take it over was just baffling,” says Christina Stile, who worked at the NICHD for over 25 years and had most recently been its deputy director of communications. “Like, how can you not have this?”

The year the Back to Sleep campaign first launched, 1994, over 4,000 babies died of SIDS. The NICHD, in partnership with the AAP and a coalition of like-minded organizations, put together pamphlets in multiple languages, VHS tapes for parenting classes, and DVDs for grandparents—all broadcasting the AAP’s findings that putting babies to bed on their backs would help reduce sleep-related death and injury. They put public service announcements on TV and radio stations. They placed the Back to Sleep messages on the packaging of Pampers diapers and baby cereal boxes. They developed continuing education courses for pediatric nurses, and outreach programs that were held at churches, a sorority, a fraternity, and other community centers.

Source: NIH Source: NIH

Around 2012, as SIDS research continued and findings evolved, Back to Sleep expanded to Safe to Sleep, to include recommendations for the baby’s surroundings and not just sleep position.

Just 10 years after the launch of the initial campaign, SIDS deaths had dropped by about half. Safety experts attribute that success directly to Back to Sleep; the messaging to parents was that simple, and that effective. In 1993, 17 percent of infants were being placed on their backs to sleep; by 2010, it was 73 percent.

In more recent years, the NICHD turned its efforts to posting on social media, hosting Reddit "ask me anything" conversations (AMAs) and Twitter chats, and creating shareable educational Instagram reels. It also hosted a Flickr account of safe-sleep photos that were free for anyone to use when publishing online.

Pediatric health experts have praised the NICHD for its success in reducing infant deaths, but caution against allowing that success to lead to complacency. The messaging needs to be broadcast constantly and consistently, they say.

Just like with “Stop, Drop, and Roll,” repetition is key, says Rachel Moon, MD, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Virginia Health Children’s in Charlottesville and the chair of the AAP’s subcommittee on sudden unexplained infant death.

“We know that the more parents are told about safe sleep, the more likely they are to do it, because they are more likely to think that it’s important,” Moon says. “The other thing is that babies are still being born and there are still people who are becoming parents who haven’t been parents before, and we need to provide this information to them as well.”

When asked about the status of Safe to Sleep, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services said that the campaign’s materials remain available to the public via its website and that “no final decision has been made regarding the future of the Safe to Sleep campaign.”

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts also say there’s much more research that needs to be done on infant sleep; there are still aspects of SIDS deaths that can’t be directly tied to suffocation that we don’t understand, and other risk factors to explore. Researchers are looking at things like how genetic abnormalities related to brainstem and cardiovascular system function may play a role in elevating the risk.

“We really need something like a cancer moonshot, but for SIDS, we need to attack this from all levels,” says Russell Ray, PhD, Associate Professor of Neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine.

To perform that research, Ray says, it’s vital to continue to collect and analyze data on every aspect of the deaths that do occur, from the medical history information of the babies to the exact positions their bodies were in when they died.

But cuts to a number of other federal data-collection projects now threaten that aim as well. This year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suspended the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) and is planning to eliminate the Sudden Unexplained Infant Death Case Registry, both programs that contributed data to researchers’ understanding of infant deaths and how and why they occurred.

SIDS and SUID Are on the Rise, With Highest Rates for Black Infants

Cuts to the Safe to Sleep campaign could be especially devastating for Black families—here’s what experts say can be done about the impact.

Meanwhile, staff cuts and leadership shake-ups have the potential to weaken the efficacy of the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the federal agency tasked with overseeing the safety of household products, including baby gear. In the past several years, the agency has taken a strong position on developing protective standards for infant sleep and maintains resources on its website for parents. (A CPSC spokesperson declined to answer media questions during the federal government’s shutdown.)

“We’ve got this perfect storm of no safe sleep education coming from the government, no data on the national level to support what’s happening, and very little way to monitor that what families are buying is safe for sleep,” says Alison Jacobson, whose son, Connor, died of SIDS in 1997; she’s now the executive director of First Candle, a safe-sleep advocacy and education organization that also offers bereavement support to parents experiencing loss. “There’s not a doubt in my mind that the number of deaths are going to go up, not a doubt in my mind.”

But, she added, since federal data collection has stopped, we won’t even know how high the toll is.

We’ve got this perfect storm of no safe sleep education coming from the government, no data on the national level to support what’s happening, and very little way to monitor that what families are buying is safe for sleep.

Executive Director, First Candle

Unsafe Imagery Inundation

The ABCs of safe sleep (Alone, on their Backs, in a flat Crib or bassinet) means, in practice: no blankets, no crib bumpers, no stuffed animals, no pillows, no loungers, no sleeping in car seats outside of the car, no sleeping on adult mattresses, no sleeping on couches or in swings, no putting babies down on their tummies, no bed-sharing.

This can feel like pretty harsh advice, as every exhausted parent of a crying baby can attest. It also doesn’t always feel intuitive: To some parents, a baby sleeping alone on their back in a bare, flat bassinet may look a bit exposed, a bit cold. Wouldn’t they be so much more comfortable on a soft pillow, or having their heads raised up a little? Just one blanket over them, maybe? What about just for naps? Can we put them to bed on their stomachs, because it just looks so much more natural? Just once?

Research shows that the extent to which we deviate from expert advice, and how often, depends a lot on what we hear from people we trust—our family and friends. Our behavior is also (consciously or not) influenced by what we see online, even if it’s content from people we don’t know.

“When you look at how people make their healthcare decisions, social media and images online play a big role in that,” says Michael Goodstein, the neonatologist and member of the AAP subcommittee on sudden unexpected infant death. “The images that show unsafe sleep undermine our messaging and really suggest to families in their decision-making that maybe those things are okay to do.”

The problem is, sleeping babies are cute. And they’re so much cuter when they look cozy. The AAP guidelines are decidedly not cozy.

This isn’t exactly a new problem. A 2009 study looked through dozens of print magazines that were geared toward new mothers and found that only 36 percent of the hundreds of photos in the magazines showed babies in a safe sleeping environment, on their backs, by themselves. Another study found a similar percentage in ads for cribs.

Social media has only accelerated our access to images and information of all kinds—it’s in our pockets, and, unlike our pediatrician, it’s available all day and all night. As a new parent, Googling a question is a reflex, like breathing. We search and post and cycle through Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Threads, TikTok, YouTube, and X for information, for emotional support, and for a sense of community in an often lonely time. And we do it while we are trying to stay awake, when we’re feeding our babies in the middle of the night.

A 2024 study analyzed baby photos shared by parents in a Facebook group discussing infant sleep, and found that only 14 percent of the photos reflected a safe sleep environment that adhered to AAP guidelines. The majority of the photos showed newborns sleeping on their stomachs or with pillows, or else images of bed-sharing, says the study’s author, Kelly Pretorius, PhD, RN, assistant professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and adjunct faculty at The University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing.

“Parents are going to social media for support: It can be information, it can be emotional, but they are seeking support, and that is where they’re finding it,” says Pretorius, who in addition to her academic and clinical work on infant healthcare, also remembers going online to try to stay awake while breastfeeding her newborn in the early days of her rigorous PhD program. “We know how much time people are spending in these forums, and that influences the perceived social norms.”

A 2021 study of images on Instagram found that only 7 percent of those images were consistent with AAP guidelines. A similar analysis in 2023 found that under 2 percent were.

Graphic: Consumer Reports, Getty Images Graphic: Consumer Reports, Getty Images

“When any product photos show babies sleeping in unsafe setups, it sends a quiet message that those risks don’t matter, and that couldn’t be further from the truth,” says Lisa Trofe, the executive director of the Baby Safety Alliance, a trade group formerly known as the Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association. Trofe added that the group is working to develop new resources that make it easier for content creators and brands to show safety the right way, and that “Most of us have been that mom scrolling at 2 a.m., looking for what’s normal, trusting that what we see is safe. That’s why it’s so important to get those images right, because we all know how much they stay with you. The more we can help parents see safety reflected in what they already follow and love, the more lives we can help protect.”

Safe sleep experts and advocates say that, ideally, platforms could put some effort into moderation of baby-sleep images online to avoid spreading potentially harmful or misleading ideas about what’s safe for infant sleep and what’s not.

When Alison Jacobson sees images of unsafe sleep on social media, especially if they are posted by big influencers or celebrities, she slides into their DMs and (politely) says that what they are showing is harmful.

Devon George, chief programs officer for Cribs for Kids, a nonprofit organization that distributes cribs to families in need, says that when she sees unsafe images on product marketing, she emails the companies with a link to her organization’s safe sleep photo guidelines and its free library of safe sleep photos. But what if some of the online platforms could do this work for them, and flag the images as unsafe as soon as they are posted?

“I would love one day for people’s hair to stand on end when they see images of unsafe sleep,” George says, “the same way it would if you saw a baby being held on somebody’s lap in the front seat of a car.”

I would love one day for people’s hair to stand on end when they see images of unsafe sleep, the same way it would if you saw a baby being held on somebody’s lap in the front seat of a car.

Chief Programs Officer, Cribs for Kids

The problem of unsafe infant sleep imagery is everywhere online—not just on social media platforms. Take, for example, the stock photographs that often accompany online news and feature articles about babies—even hospitals’ blog posts about postnatal care—which can potentially confuse or mislead new parents by showing newborns sleeping on their stomachs, or with a blanket, or on a pillow.

Michelle Barry, president of the nonprofit group Safe Infant Sleep, says that she often sees unsafe stock photographs being used online by sleep consultants or small businesses that sell baby products. But she knows that’s because the stock photography databases simply don’t have that many safe options to choose from. Whenever she contacts them to ask if they would use a safer photo, she says, “time and time again they tell me, ‘I can’t find any that I haven’t already used.’”

In a 2017 study of nearly 1,950 stock images online, researchers found that just about half of them showed babies sleeping on their backs, and only 5 percent of them showed an entirely safe sleep environment.

Then, once you shift from scrolling through content to shopping online—sometimes without even changing apps—that’s when the mixed messaging about infant sleep starts getting especially hard to ignore.

Sleepless and Shopping the Endless Scroll

There are a lot of internal contradictions in the very eye-catching Amazon listing for the FNFURUG baby lounger, described as a “Baby Lounger for Newborn 0-24 Months, Baby Nest Snuggle Me Lounger Cover Soft Breathable Cotton, Newborn Essentials for Baby Boys & Girls Gift, Portable Infant Lounger for Home and Travel.”

It’s plastered with photoshopped images of sleeping babies, right next to a product description saying that it is definitely not a sleeping device. Rufus, Amazon’s AI-powered chat, answers the question “should this be a co-sleeping device?” with the answer, “No, this baby lounger is not intended for co-sleeping. The product instructions explicitly state that it should never be used as a co-sleeping device.” But the chat box pops up right next to the seller’s photo of the lounger being used as a co-sleeping device.

Source: Amazon Source: Amazon

For years, infant loungers like the DockATot were marketed as the “safer way” to bed-share, or co-sleep. Parents may see the loungers as a way to protect their babies from adults rolling over them in their sleep, without realizing that their soft sides, bases, and shapes put the babies at risk of suffocation.

Since the CPSC passed a new safety rule in response to dozens of infant deaths, manufacturers of baby loungers and other infant pillows may not market them for sleep. Manufacturers must clearly state that soft or inclined products like these are intended for supervised, awake playtime only. The CPSC announces recalls of products like these all of the time. And according to incident reports sent to the agency, babies continue to die in loungers when they are put to sleep in them.

This particular lounger listing seems to have replaced the word “sleep” with the word “play” throughout its marketing language in order to skirt this regulation. So the product page says, “Give your baby a comfortable play space” . . . next to a photo of a sleeping baby. Another caption says, “Make the baby feel secure and play soundly” . . . next to another photo of a sleeping baby. Five-star user reviews of similar loungers are accompanied by happy customers’ photos of their own babies sleeping in the loungers at home.

What’s going to stick in the mind of a sleep-deprived parent scrolling in the middle of the night: a disclaimer in the product description, or a blur of images of peacefully slumbering babies?

Amazon told CR that the company uses both human investigators and machine-learning programs to monitor its site for products and listings that don’t comply with its policies, and that it is continuously refining and improving its process. Whenever CR has pointed out misleading, dangerous posts like this in the past, Amazon has taken them down, and that is what happened with this one as well.

But the game of whack-a-mole continues. Amazon is far from the only platform littered with listings like these; loungers are marketed to tired parents on other retail sites and apps with similarly confusing messaging. The FNFURUG is just one example of how misleading and potentially harmful information is coming at parents from all sides when we shop online.

CR contacted Target, Temu, and Walmart to ask them how they monitor unsafe sleep imagery and product descriptions. Walmart said that it uses both AI tools and human oversight to monitor its site, and that it swiftly removes listings that violate its policies. Temu declined to comment, and Target did not respond.

When it comes to social media shopping platforms like Instagram Shop and TikTok Shop, the responsibility for safe messaging can be even murkier, as the line between happy customer and sponsored post can be fuzzy.

In one Instagram post, a mom influencer “unboxes” and then raves about a lounger by Rahoo Baby. “Ergonomic design for lounging, tummy time. For baby’s awake time, not for sleep 😉,” she writes in the caption, below a video of her baby sleeping. The wink emoji, combined with the video of her baby sleeping on the lounger, would seem to suggest using the lounger for infant sleep. Many influencer-hopefuls include brand names and hashtags on their posts in the hopes of attracting paid sponsorships, “gifted collabs,” or free samples from those brands; this one seems to have achieved that goal, since in her caption, she thanks Rahoo Baby for the gift.

Source: Instagram Source: Instagram

It’s unclear whether Rahoo Baby approved this post, and Rahoo’s official Instagram account and website don’t endorse using its products for baby sleep. But if you search Instagram for “baby lounger,” this post—and its decidedly mixed messaging—pops up.

CR reached out to this Instagram user, Rahoo Baby, and Meta, the parent company of Instagram, with questions, but none responded.

On TikTok Shop, influencers can post videos about stuff they like, and when viewers swipe over to their “shops,” the posters get a commission for each sale. It’s a wild west of recommendations from parents who swear by their newborn head pillows, their weighted baby swaddles, and their thick braided crib bumpers, all of which are unsafe, according to the CPSC. Search TikTok for “baby loungers” and you’ll see videos of people holding up their squishy, pillow-like loungers that they say are “designed to make co-sleeping safer,” and “great for co-sleeping . . . with your newborn,” all while earning commissions via the platform on sales of baby loungers that are not supposed to be marketed for infant sleep.

CR reached out to these TikTok influencers with questions but did not receive a response. When asked about these videos and the company’s policy generally toward infant sleep products, TikTok told CR that co-sleepers (along with weighted baby swaddles, drop-side cribs, and crib bumpers) are prohibited from TikTok Shop and that all co-sleepers have now been removed from the shop.

Source: TikTok Source: TikTok

The Feedback-Loop Effect

As anyone who has used social media for 5 minutes knows, the algorithm learns what you like and feeds you more of the same. It’s value-neutral: it can reinforce a safe message, or an unsafe one. It only wants your time and attention. And if you’re a tired parent having a really hard time following those ABCs of safe sleep, you’re a ripe target for posts telling you that you really don’t have to anymore.

The algorithm learns what you like, and feeds you more of the same. It can reinforce a safe message, or an unsafe one. It only wants your time and attention.

“If you see someone come on Instagram and speak with conviction from their living room about how bed-sharing is the safest thing to do, and you watch that whole thing through, the algorithm is going to serve you up five more videos to serve that same narrative,” says Dani Morin, the online workshop host. “You’re online and you’re searching for anything to help, and anything that’s going to lead you down the path that you already kind of want to take. And then you share it to your community, and the snowball effect happens.”

With the increasing ubiquity of AI chat programs like ChatGPT, and AI-assisted search like Google’s Gemini and AI Overview, the self-reinforcing feedback loop that’s so evident in your social media algorithms is now becoming part of your search experience, too. The answer you get will depend very much on how you phrase your question.

When CR recently asked ChatGPT the specific question, “Are DockATots safe?” the answer came back clear: “The short answer: No, DockATot is not considered safe for unsupervised sleep,” and “the consensus across pediatric experts is that it’s never appropriate for child sleep, nap, or overnight use.”

However, when asked the more open-ended and slightly leading question “what can I buy to safely bed share,” ChatGPT offered up a list of in-bed co-sleepers and nests, “best for newborns to 3-6 months.” The DockATot Deluxe+—a product CR has warned parents about—was the second product. It’s almost like it told us what we wanted to hear.

OpenAI, the creator and owner of ChatGPT, did not respond to CR’s request for comment.

Meeting Parents Where They Are

Almost everyone interviewed for this story said the rise of the influencer economy—and the rise of our reliance on AI—also both happen to coincide with an increasing cultural distrust in those traditionally positioned as experts: doctors, scientists, researchers, and professors.

“When people see a doctor talking on a video about what’s important, they don’t always take it the same way they do when they see another parent,” says Shayna Raphael, a parent and safety advocate who posts videos about safe sleep on Instagram and TikTok. “You have these moms with millions of followers, showing their use of these products and saying that they’re safe, and people will listen to those parents way more than they’re going to listen to the AAP.”

Like her friend Morin, Raphael came to her passion for advocacy the hardest way. Raphael’s 10½-month-old daughter, Claire, died in 2015 when she suffocated during a nap at day care. As Raphael would later learn from Child Protective Services and medical reports, Claire had been put down for a nap on a soft adult mattress, and her sleeping body formed a small pocket of air that Claire’s breath filled with carbon dioxide. Claire breathed and re-breathed the same air again and again until she died.

Morin agrees with Raphael’s assessment of how social media has helped amplify voices other than—and often opposed to—traditional experts. While she celebrates the potential of social media to help spread the word about safe sleep practices, she feels that those views are in the minority at the moment.

“The pendulum will swing back,” Morin says, “but right now we are very much in an anti-expert, anti-doctor, ‘I am my own boss’ era.”

Raphael says that it took two years after Claire’s death to be able to, or even want to, speak about it publicly. But eventually, she set up a foundation in her daughter’s name, and she’s active on social media, posting videos with baby safety tips and announcements of product recalls. She spends a lot of time answering her followers’ questions in multipart videos on Instagram and TikTok.

“Claire should be starting middle school this year,” Raphael said at the end of a recent TikTok video. “We just passed the 10-year anniversary without her, and her death was absolutely preventable. Safe sleep saves lives.”

A lot of her followers want to hear what happened to Claire, and Raphael patiently tells the story, and answers the questions, over and over. Some of her viewers have commented that hearing her story has persuaded them to change their own baby-sleep practices for the better.

“It’s harder to dismiss someone who’s actually gone through it, and who’s sharing it because they never want anyone else to go through what they went through,” Raphael says.

Source: Instagram Source: Instagram

Raphael has also run trainings for state health and child safety departments, teaching them about how to use social media effectively to spread their public health messages. Videos of doctors in lab coats ticking through the ABCs of safe sleep may not be the most appealing or viral content, she says, but there are ways to engage with tired parents about safety in a way that meets them where they are, both psychologically and literally. Lectures may not work, but stories do.

Cribs for Kids organized a Safe Sleep Storytime social media campaign for October—Infant Sleep Awareness Month—which collected personal stories from parents, advocates, and first responders to illustrate why safe sleep is so important, even when it feels impossible.

Safe-sleep researchers agree that there is great, and mostly untapped, potential here. Parents are turning to social media for support, and so that’s where they should get it. Pamphlets picked up at the hospital right after giving birth can’t compete with the dangerous imagery and messaging parents face online every day (and night) afterward, every time they pick up their phones. That’s why safety information and guidance needs to reach parents right there, on the platforms where they’re already spending so much time.

This strategy needs to go beyond commenting “this is actually wrong,” on Instagram and TikTok posts, says Kelly Pretorius, the assistant professor at Baylor. It’s not an effective way to combat misinformation, and the tone can be off-putting. Putting out safety tips on the official social media accounts of local health departments won’t cut it, either, because the average person probably isn’t following those accounts.

“I think we would have more success with targeted advertising and partnering with influencers,” Pretorius says. “I know this may not be realistic, but I would also love to have a pediatric expert available 24/7 on social media, and I would love for it to be covered by insurance.”

Maybe the only way to turn the tide of misinformation, misleading imagery, false expertise, paid influence, and bad Photoshop is to flood the algorithm with the right stuff. Unfortunately, flooding the algorithm takes resources, policy changes, and a unified, evidence-based message—all the things that a fully funded federal Safe to Sleep campaign had previously promised.

“We need a new approach, and we need it to be run by a national campaign, to have it be something bold enough to really permeate and influence the social norms, which is why we’re all so concerned about the recent funding cuts,” Pretorius says.

Many safe-sleep researchers have said that having to go back to work immediately after having a baby compounds the parental exhaustion and desperation, and therefore the danger.

“I think we need to come at this with very deep empathy for what parents are facing in our society today, and understanding the parental stress and the lack of sleep and support,” Pretorius says.

In other words, “Safe sleep is hard, you know?” says Devon George, the chief programs officer at Cribs for Kids. “It’s really, really hard. So how can we support families as they go through this?”

Safe Sleep Guidelines for Infants

Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID), which includes sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), remains a leading cause of death in infancy. But following safe sleep practices every night and for every nap can help keep your infant safe and prevent the risk of SUID fatalities. For more safe sleep recommendations, contact your pediatrician.

- Always place your baby down on their back in their own sleeping space, with no other people or pets.

- Always use a crib, bassinet, or portable play yard—with a firm, flat mattress—for sleep.

- Only use a fitted sheet in your baby’s sleeping space.

- Do not put loose blankets, pillows or nursing pillows, stuffed toys, bumpers, baby loungers, or sleep positioners in your baby’s sleeping space.

- Do not use weighted sleep sacks.

- If your baby falls asleep in a car seat, stroller, swing, or infant carrier, move them to a firm sleep surface on their back as soon as possible.