Instacart’s AI-Enabled Pricing Experiments May Be Inflating Your Grocery Bill, CR and Groundwork Collaborative Investigation Finds

A Consumer Reports and Groundwork Collaborative investigation found that some grocery prices differed by as much as 23 percent per item from one Instacart customer to the next. In an inadvertently sent email, the company calls one pricing tactic “smart rounding.”

Update Dec. 22, 2025: Prompted by this investigation, Instacart has stopped offering technology that allowed grocery retailers to charge shoppers different prices for the same groceries at the same time. Learn more about that change, as well as legislative and regulatory responses to our findings.

This article is part of Consumer Reports’ Make the Price Right series, which launched with our investigation into pricing inaccuracies at Kroger stores.

Testing, research, and analysis by Derek Kravitz, Angel Han, and Alan Smith of Consumer Reports; Lindsay Owens and Katie Wells of Groundwork Collaborative; and Eric Gardner of More Perfect Union. Statistical analysis by Debasmita Morgan and Nayeon Kim for Consumer Reports. Data visualizations by Evan O’Neil.

Many U.S. shoppers who order grocery deliveries through Instacart are unknowingly part of widespread AI-enabled experiments that price identical products differently from one customer to the next—sometimes by as much as 23 percent. Instacart’s algorithmic pricing experiments were found to be occurring through the platform at several of the nation’s biggest grocery retailers, including Albertsons, Costco, Kroger, Safeway, Sprouts Farmers Market, and Target. These are among the findings of a monthslong investigation by Consumer Reports and Groundwork Collaborative, as part of a larger project with More Perfect Union, two nonprofit organizations with experience analyzing food prices.

Algorithmic pricing is usually invisible to consumers, who typically see only the prices and fees they’re offered. Researchers, meanwhile, are rarely granted access to the complex systems of algorithms, artificial intelligence, and data that parcel out individualized prices. CR’s investigation, which involved orchestrating simultaneous online shopping sessions with hundreds of volunteers, aimed to peek inside the black box.

Instacart has disclosed its pricing experiments in corporate marketing and investor materials, noting that “shoppers are not aware that they’re in an experiment.” But the company described the resulting price differences as small and “negligible.”

Our investigation suggests that the scope of Instacart’s price experiments—which are taking place against the backdrop of the fastest increase in food prices since the late 1970s—is far broader and more costly to some consumers than has been publicly acknowledged. Every one of the volunteer shoppers who participated in our tests was subject to algorithmic price experiments.

In response to our questions, Instacart confirmed that our findings accurately reflect its pricing experiments and strategies, which it said were ongoing at 10 partnering grocery retailers at the time of our investigation. The company declined to name them, however, and said the experiments affect only a small portion of its retail partners, have a limited impact on consumer pocketbooks, and are similar to well-established in-store pricing practices.

“Just as retailers have long tested prices in their physical stores to better understand consumer preferences, a subset of only 10 retail partners—ones that already apply markups—do the same online via Instacart. These limited, short-term, and randomized tests help retail partners learn what matters most to consumers and how to keep essential items affordable,” the company wrote in a statement. (See additional Instacart responses, below.)

Charging different amounts to different customers for the same products is not illegal or new. U.S. consumers have grown accustomed to paying different prices for the same airline seats, event tickets, hotel rooms, rideshares, and certain other goods and services that are subject to rapidly changing shifts in supply and demand.

But consumers express deep misgivings about algorithmically driven changes in pricing when it comes to more essential goods like food. A nationally representative CR survey of 2,240 U.S. adults conducted in September 2025 found that 72 percent of people who have used Instacart in the previous year did not want the company to charge different users different prices for any reason. Instacart shoppers we spoke to say they were unaware that they were participants in active Instacart pricing experiments and view the practice as manipulative and unfair.

Experts also warn that algorithmic pricing—when combined with artificial intelligence and the massive amounts of personal data collected on U.S. consumers—could evolve into a more pernicious pricing strategy called “surveillance pricing,” which involves using personal characteristics, behaviors, and things like your shopping history to set individualized prices.

“All of us, without our knowledge, are being conscripted in this enormous and growing social experiment being conducted by companies across a wide range of industries,” says Len Sherman, an adjunct professor and executive-in-residence at Columbia Business School in New York City, whose research examines the proliferation of algorithmic pricing. “Every step that we take as a consumer is being bundled together in these massive databases and being analyzed so that the next time we confront a purchase decision, everything we’ve ever done is going to factor into the price we see.”

What Our Instacart Investigation Found

CR chose to look at Instacart because it is by far the dominant e-commerce grocery delivery platform in the U.S., with nearly 250 million orders fulfilled in the first three quarters of 2025. The company calls itself “the largest online grocery marketplace in North America.” Instacart says that its service is particularly valued by seniors, those living in rural areas and so-called “food deserts,” and those with disabilities. The company also offers special promotions for customers using federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, including $0 delivery fees on their first three orders and 50 percent off the Instacart+ premium service for the first year.

We solicited volunteers from across the country to participate in the investigation, starting with previous participants in CR’s Community Reports projects. In September, the 437 volunteers were divided into four groups. During a video meeting for each group, the volunteers simultaneously shopped on Instacart for identical baskets of 18 to 20 goods from the same retailers, Safeway and Target. A fifth test looking at Safeway and Target was conducted in person with volunteers in Washington, D.C. This process enabled us to control for some of the factors that might have influenced the prices the shoppers saw, including the specific store they shopped at, the time of day, and the day of the week.

In each case, the shoppers placed the items in their virtual shopping carts and recorded the prices by taking screenshots but did not purchase the goods. After checking the screenshots of our volunteers and evaluating roughly 200 that had no errors, we found that every shopper was an unwitting participant in Instacart’s pricing experiments.

And in a final test, conducted online with volunteers in November, we looked at Instacart purchases at additional grocery retailers and found evidence of price experimentation at four additional chains: Albertsons, Costco, Kroger, and Sprouts Farmers Market.

About three-quarters of the products we checked were offered at different prices to different customers. Some products were offered at as many as five different prices, and price variations for the same products ranged from as little as 7 cents to $2.56 per item.

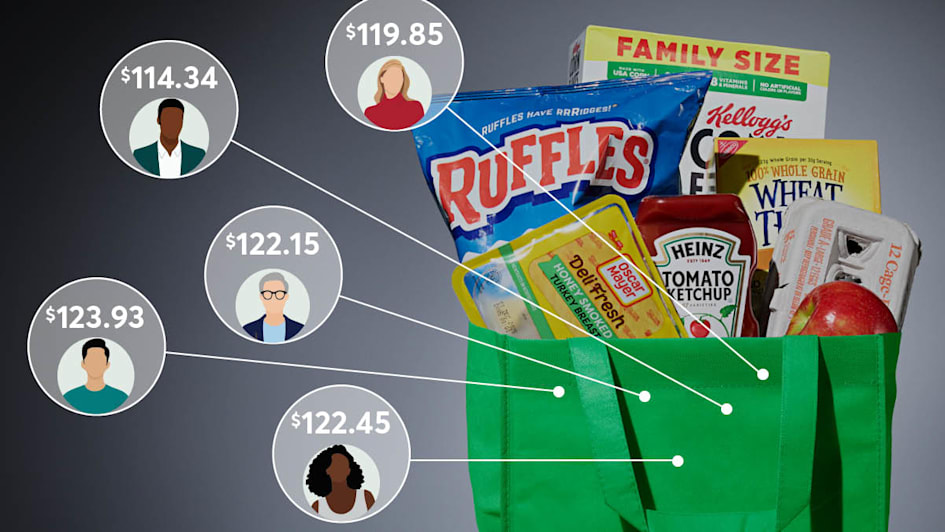

In one test, conducted on Sept. 4, 2025, 39 volunteers used Instacart to shop at a Safeway in Seattle. Each placed 20 different products in their virtual grocery basket and captured a screenshot of the prices.

Instacart offered most shoppers the same basket of groceries at 5 different prices, ranging from $114.34 to $123.93.

The difference between the lowest and highest priced baskets was $9.59, or 8.4%.

We found no price variations for some products, including Premium brand saltine crackers, Heinz ketchup, and Barilla farfalle pasta.

Other products showed moderate price variations, such as Cheerios cereal, Ruffles potato chips, and Lucerne eggs.

And some items varied more dramatically in price.

We also saw that those seemingly small price variations could add up to big differences in the overall cost of groceries. The price of the same basket of food at a Seattle-area Safeway on the Instacart platform, for example, ranged from $114.34 to $123.93—roughly a $10 difference. And only 8 percent of those shoppers got the lowest basket total.

Based on how much Instacart says the typical household of four spends on groceries, the average price variations observed could translate into a cost swing of about $1,200 per year.

Instacart has been transitioning from a company that primarily delivers groceries to one that sells a range of digital tools to help grocery retailers and manufacturers increase sales. “We’re not just a marketplace,” CEO Chris Rogers told investors during a November earnings call. “We’re the leading technology and enablement partner for the grocery industry.”

After acquiring a small AI company called Eversight in 2022, Instacart began offering pricing software to retail companies as a way to “optimize” grocery prices and to tailor prices, promotions, and discounts. Instacart claims the technology can increase grocery store sales by 1 to 3 percent and “incremental margins”—the extra profit a company gets from each additional sale—by 2 to 5 percent.

The pricing tactics we observed indicate some of the ways Instacart is doing that.

We found that Instacart repeatedly showed different customers different “original” prices for the same discounted item, making the purported savings appear larger or smaller, depending on which group they’d been sorted into. For example, most volunteers shopping on Instacart at a Safeway in Seattle were shown original prices for Premium brand saltine crackers of $5.93, $5.99, or $6.69, while the final sale price was the same for everyone—$3.99.

Even though many U.S. consumers are already cynical about inflated “original” prices, behavioral economists have demonstrated that the tactic—known in the field as false reference or fictitious pricing—can be effective at getting consumers to buy more. Fictitious pricing is widespread among retailers and is being “turbocharged by dynamic pricing algorithms,” says Laura Smith, the legal director of the nonprofit Truth in Advertising. “These phantom discounts, which often manufacture urgency to convince shoppers to part with their money, harm consumers and distort competition in the marketplace,” she says.

We also found that Instacart was conducting elaborate tests in which it systemically increased and decreased the prices of products, mostly in 10-cent increments, across large cohorts of customers. For example, when our volunteers shopped at a Target in Ohio, nearly all of them were grouped into one of four different grocery baskets, ranging from $84.43 to $90.47—a difference of $6.04. In the most expensive cart, apples, carrots, Ruffles potato chips, Wheat Thins, Premium saltines, Cheerios, Clif Bars, Quaker oats, and Oscar Mayer sliced turkey were each 10 cents to $1 more per item more than in the least expensive cart.

Why Instacart Is Conducting Price Experiments

Experts who examined our findings told us Instacart and its partners appeared to be trying to determine how “price sensitive” consumers are—that is, how high a retailer could raise the price of an item before customers decide not to buy it.

That motive was confirmed by an email exchange between Instacart and Costco that was accidentally sent to CR by Costco after we contacted the company for comment on our findings.

In the email, an Instacart employee wrote that the company had been experimenting in recent months with what it calls “smart rounding” at Costco. Instacart described smart rounding in a 2023 letter to company shareholders as a “machine learning-driven tool that helps retailers improve price perception and drive incremental sales.”

The letter goes on to explain that “by thoughtfully pricing certain items with high or low price sensitivity, retailers have seen customers’ overall price perception improve and their engagement increase as a result. For some of our major grocery partners, this has led to millions of dollars in annual incremental sales.”

Sales

Surplus

Instacart’s data-driven push to increase sales and maximize profit margins is a reaction to similar approaches by two bigger retailers, Amazon and Walmart, says Errol Schweizer, a grocery industry consultant who, as an executive at Whole Foods, helped set up the company’s partnership with Instacart. “This pricing gamesmanship, it’s all to keep pace with the competition and to wring a few more pennies out of people,” he says. “And as things get more competitive for grocers and suppliers, it’s going to get more and more complicated, wackier, and out of control for the customer. By the end, it’s predatory and manipulative.”

Instacart has grown quickly, even while wrestling with intense competition from in-house grocery delivery services and competitors like DoorDash and Uber Eats. The company turned a profit for the first time in April 2020, three years before going public on the New York Stock Exchange. The company doesn’t break out what it makes on its pricing software, but “advertising and other revenue”—meaning the money from things other than store orders—grew to nearly $1 billion in 2024, up from $295 million in 2020.

Instacart Responds to Our Findings

Instacart says only 10 of its retail partners use its Eversight pricing tools, but it would not name those companies or say what percentage of its customers are being offered different prices than other consumers. Our investigation found Instacart to be conducting algorithmic pricing tests at one major retailer, Target, that says it is not among the 10 Eversight retail partners.

Specifically, when we contacted Target about our findings, the company told us it had no business relationship with Instacart. Instacart subsequently acknowledged that it scrapes Target’s publicly displayed prices and charges an additional amount to offset its “operating and technology costs.” But Instacart did not explain why it was also conducting price experiments at Target.

Instacart repeatedly told CR that its retailer partners “set and control their own prices on Instacart.” But that claim, too, is contradicted by our findings at Target, which has no formal business relationship with Instacart. Instacart told CR it has now stopped its price experiments at two retailers where we found evidence of such experimentation, Costco and Target.

Instacart also maintains that customers it conducts pricing experiments on do not, on average, end up paying more because of it.

“Some consumers may see slightly higher prices for certain items and lower prices for others; however, most customers see the standard price,” Instacart’s statement reads. Our findings, though limited, don’t align with that assertion either. Across the five tests in which our volunteers priced baskets of the same 18 to 20 popular foods, the least and most expensive carts differed by an average of about 7 percent of the total cost.

Safeway (which is owned by Albertsons), Costco, and Kroger did not respond to questions about Instacart’s price experiments. Sprouts declined to comment.

Alex Tolley

How Retailers Are Laying the Groundwork for Surveillance Pricing

Retailers are now using AI and other technologies to create detailed profiles on their customers, with the potential to personalize prices and discounts down to the individual shopper.

Instacart denies that its price experiments use any personal or demographic data, and says customers are randomly assigned to price testing cohorts by product category and location.

Our investigation found no evidence to suggest otherwise: Our sample of volunteers would need to be larger to find statistical correlations between their demographic data and the prices they were offered. And our participant pool was not representative of the U.S. population.

But experts who evaluated our findings found them to be robust and meaningful, and those who study algorithmic pricing suspect Instacart and other retailers are collecting personal data, in part, to personalize prices. In fact, CR has also found that Instacart has obtained personal data from two of the largest data brokers in the U.S., Acxiom and Epsilon.

Instacart denies that it uses any personal data to set grocery prices. But the company did acknowledge that food brands may use behavioral data for discounts or promotional offers through its Eversight software, using a tool it calls Offer Innovation, which enables price experiments similar to those that our investigation observed.

One example of the kind of behavioral data that might be used is a metric called “new-to-brand,” which identifies new or returning customers and could be used to test whether they react differently to price changes compared with repeat customers.

Multiple Instacart and Eversight patent applications submitted between 2017 and this year explicitly reference the use of personal, behavioral, and demographic data to help tailor promotions and discounts, which affect final prices, and group certain customers together into customer “subpopulations.” These groupings could be defined by factors such as previous purchase history—which industry analysts say is the most important single data point for retailers—as well as buying behavior and demographic characteristics such as age, gender, household size, and household income.

When we asked Instacart about the demographic and other personal data listed in its patents, the company maintained that patent applications routinely use overly broad and “all-encompassing” language in order to “protect innovation and preserve optionality.”

Given the financial incentives for retailers to try surveillance pricing, however, and the current lack of regulation, several consumer advocates and pricing experts we spoke to are unsatisfied by that explanation. “Once the technology is in place, even if they aren’t doing it now, with the press of a button, they could certainly start using it to profile shoppers both online and in store,” says Phil Lempert, a grocery industry analyst who runs the website SupermarketGuru.

Some retailers have already crossed this threshold. Kroger, for example, one of the nation’s largest grocery chains, has acknowledged using demographic data and purchase history in the various promotions and discounts it routinely offers its loyalty program members.

“This isn’t new. It’s the age-old dream of retailers to charge every person their absolute maximum price, now supercharged by data,” says Lina Khan, who served as chair of the Federal Trade Commission from 2021 until January 2025 and is now a professor at Columbia Law School. “We are moving from a transparent market with public prices to an opaque world where we are alone against secret algorithms. We must stop asking if this is okay and start asking if we should ban these practices entirely before it’s too late.”

Dianna Dance-Lewis

‘THIS PRICE WAS SET BY AN ALGORITHM USING YOUR PERSONAL DATA’

In 2022, under Khan, the FTC published guidance stating that unfair pricing may include “price discrimination not justified by differences in cost or distribution.” And in 2024, the agency sought information from eight companies that offer individualized pricing technology and issued a preliminary finding that “retailers frequently use people’s personal information to set targeted, tailored prices for goods and services.” The FTC told CR in December that the agency’s work in this area is ongoing and “our study’s findings will be released to the public when it’s concluded.”

Several states have introduced legislation to address algorithmic pricing practices. A first-of-its-kind New York state law went into effect in November, requiring most companies to include a prominent disclaimer on algorithmically set prices that says: “THIS PRICE WAS SET BY AN ALGORITHM USING YOUR PERSONAL DATA.” And several states, including California, Colorado, and Pennsylvania, have introduced bills that would go further by altogether banning surveillance pricing by certain types of retailers, including grocery stores. (CR policy advocates have supported several of these measures.)

Meanwhile, the next frontier in algorithmic pricing may be in the aisles of your local grocery store.

Like many retailers, Instacart has been piloting the use of electronic shelf labels, or ESLs—digital price tags that enable retailers to rapidly and remotely change shelf prices. In July 2024, Schnuck Markets, a grocery chain with more than 100 stores throughout the Midwest, announced it would roll out new Instacart-connected electronic price tags. The software for these digital labels is called Carrot Tags, after Instacart’s carrot logo.

Until recently, the Carrot Tags website informed prospective retailer customers that the technology could be used to test prices on in-store customers. “Fully unlock the potential of ESLs’ instant and accurate pricing changes with dynamic price and promotion optimization strategies at the shelf,” the site said.

When we asked Instacart whether its Carrot Tags were being used this way in physical stores, Instacart said the ability to experiment with prices was “not currently integrated with Carrot Tags.”

Shortly after our inquiry, the website language was deleted—for accuracy, the company said when we asked.

See the Data Behind Our Investigation

Consumer Reports and the Groundwork Collaborative conducted their own tests of Instacart’s pricing algorithm, relying on more than 400 volunteers participating in live, online shopping sessions. Check out the data.

Lynn Folk

How You Can Save Money When Shopping for Food

So how can consumers save money at the grocery store and ensure they are getting the lowest possible price? Shopping in person, of course, will usually result in you paying the same amount as other customers. And CR has compiled expert strategies for saving money when shopping for food.

Here are a few of the most effective tips.

Plan before you shop. Shopping lists can help limit impulse purchases and save time. And building your list around meal planning can reduce loads of food waste—which can cost a family of four $1,500 a year, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Compare unit prices. It can be hard to compare prices when products come in a range of sizes. One solution? Focus on the price per pound, ounce, or count. Some stores routinely display these unit prices. If not, download a unit price calculator app on your smartphone.

Buy in bulk. A recent CR analysis found that warehouse clubs such as Costco, where products are mostly sold in large quantities, typically offer the best per-unit prices.

This work is made possible, in part, by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. CR’s work on privacy, security, AI, price transparency, and financial technology issues is also made possible by the vision and support of the Ford Foundation, Omidyar Network, Craig Newmark Philanthropies, and Heising-Simons Foundation.