Inside Kroger's Secret Shopper Profiles: Why You May Be Paying More Than Your Neighbors

Thanks to a state law, some consumers can find out what info companies collect and share about them. In Kroger’s case, the answers could have a direct impact on your pocketbook.

Almost everything in the private file that the Kroger grocery store chain keeps on Hazem Salem of Happy Valley, Ore., is wrong.

Salem, a married father living in the Portland metro area, is a man, not a woman.

The Salems are a family of three, not two.

His Kroger shopper profile puts Salem’s education level at a high school degree. In fact, he graduated from college and is now an electrical engineer.

Kroger estimates that Salem makes about $66,000 a year. In reality, he makes much more than that—in the six figures.

Kroger also infers that Salem is very likely to want to go on a cruise. He doesn't.

… that he’s more likely to travel internationally than within the U.S. He actually travels far more domestically.

… and that his family probably has a dog or a cat. They don’t own a pet at all.

One of the few things that Kroger gets right about Salem is how disloyal of a customer he is, despite being in the company’s free loyalty program, which promises hundreds of dollars in personalized savings on groceries and gas in exchange for providing personal info about yourself, like your name, home address, email address, and phone number. Even though he lives just a few blocks away from a Kroger-owned Fred Meyer grocery store, Salem shops there only occasionally—for special brands of things like oat milk and Tillamook ice cream that he can’t find elsewhere. For most of their food, the family opts for the lower-priced WinCo Foods, which is farther away.

“It’s creepy how much they assume to know about me, and it’s basically all wrong,” Salem said in an interview with Consumer Reports. “And it makes me less likely to want to go there, frankly.”

As a result of being deemed “non-loyal” to Kroger in his 62-page shopping profile, which CR obtained after Salem filed a formal request with Kroger through Oregon’s new data and privacy law, Salem is also likely to get fewer of Kroger’s best discounts.

Kroger doesn’t “disclose information on how many of Kroger’s loyalty members are deemed ‘loyal’ or the factors we use when creating this group, as this . . . is Kroger’s proprietary and confidential information,” a company spokesperson told Consumer Reports in a statement. Discounts are sent weekly by email or in the Kroger mobile app, where members can digitally “clip” the ones they’re interested in. Kroger makes clear that it doesn’t personalize the underlying prices of its products, only the specific discounts it offers its loyalty members. In a statement to CR, Kroger says the chief factor it relies on to offer discounts is a “customer’s prior purchases at Kroger stores and their interactions with Kroger.”

“Kroger does not personalize prices on its products,” the company said in the statement. “Kroger presents customers with available offers that Kroger believes will be the most relevant and thus the most valuable to them.”

But Kroger also uses other methods to personalize its discounts. While Kroger says purchase data is the “most determinative factor” for its promotional offers, the company says it also may use “demographic or online behavioral data” that “can be helpful to filter our audiences so that Kroger customers are presented with the relevant offers that they can use to achieve greater savings at our stores.”

That means the errors on Salem’s Kroger shopper profile, such as incorrectly stating he has only a high school education and an income that’s not in the six figures—coupled with his infrequent shopping at the chain—might play a role in why he’s not considered worthy of more discounts.

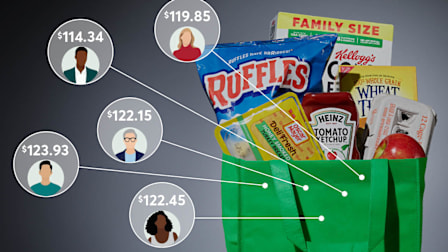

The result: With all that personalization, and the potential for errors and inaccuracies, it’s increasingly difficult to know if a reduced price is unfairly being offered to only some consumers and not others. Kroger says its customers can submit a request to correct any information they think is wrong. But many Kroger shoppers we spoke to don’t know that this information is even collected by the grocery chain.

"It’s bad enough that personalized grocery discounts could mean you pay more than your neighbor,” says Matt Schwartz, a Consumer Reports policy analyst who focuses on privacy issues. “It’s especially unfair if those discounts are based on personal information you likely didn’t even know companies were collecting.”

Coupon Conundrums

Personalized discounts can exacerbate existing wealth inequalities, experts say.

“The way this data is being used is very clearly widening the gap between upper, middle, and low-income households, and unless regulators take action, it will only get worse,” says David Friedman, a professor and dean at Willamette University in Oregon and a nationally recognized expert in consumer trade practices law.

Kroger, one of the nation’s largest grocery chains and one of the most advanced when it comes to tracking shoppers’ purchases and behavior through analytics, keeps reams of data about its roughly 63 million customers. For years, Kroger has made a concerted effort to drive people to its loyalty program and more than 95 percent of customer transactions are tied to a Kroger loyalty card.

The grocery chain also has an in-house data unit—called 84.51°, which refers to the longitude and latitude coordinates of its Cincinnati headquarters—that is tasked with collecting and analyzing shopper data to create personalized discounts, including those for its “private label” Kroger-brand products and grocery items sold by major food brands, such as Conagra Brands, the company behind Chef Boyardee, Orville Redenbacher’s, Hebrew National, and Slim Jim.

But increasingly, Kroger has another lucrative side business: Its privacy policy makes it clear that it can take the data on shoppers like Salem, repackage it, and sell it to other companies that use it for marketing and advertisements. In an investor call in 2021, a Kroger executive underscored the value of such shopping data. “The result is a longitudinal view of purchase behavior, anchored in 10 petabytes of consumer behavior data, which is extremely valuable to CPG [consumer-packaged goods] brands and sets the foundation for media activation opportunities,” she said.

Kroger’s “precision marketing” division made an estimated $450 million in profit in 2023, $527 million in 2024, and could see profits of $825 million in 2027, according to Guggenheim Securities, an investment banking company. (Kroger doesn’t publicly release division-by-division profits.) The growth of what Kroger calls its “alternative profit” business, which includes its marketing unit, has helped the grocer, despite low margins in its actual grocery stores, report record earnings, including $3.85 billion in operating profit last fiscal year.

Kroger’s “alternative profit” business now represents more than 35 percent of the company’s net income.

As a result, Salem’s report may have been sent to more than 50 different U.S. companies, Kroger acknowledged to him in writing. They include two tobacco companies, one of the country’s largest data brokers, financial institutions, and a host of analytics and marketing firms that could result in unwanted solicitations and spam.

And there are other companies that Kroger customers could object to having their data sold to, such as Soda Health, a healthcare tech company that works with health insurers, and Solutran, a fintech payments platform that helps process Electronic Benefits Transfer, or EBT, benefits for the federal government’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). This is particularly concerning for some shoppers because Kroger’s privacy policy states, “Where permitted by applicable law, to serve you better we may make certain inferences about you based upon your shopping history that are health related.”

In a statement, Kroger says it discloses shopping “basket data” to Soda Health and Solutran to “validate product eligibility to enable customers to purchase these products with the benefit cards” those companies administer. Kroger says it also sells “limited point of sale data” to the Altria Group and Reynolds, two of the nation’s major tobacco companies, for unspecified “merchandising discounts.”

In 2023, The Markup, a news site focused on technology, found marketing brochures and websites for Kroger’s in-house data unit, 84.51°, that highlighted the company’s extensive use of customer data, including demographic info. That report uncovered a marketing website that referenced an ethnic panel of Hispanic shoppers and another page that claimed Kroger had data on 2 billion annual transactions "across 60 million households with a persistent household identifier”—a unique ID that can be traced back to an individual consumer.

That 84.51° website has since been updated to remove the reference to “60 million households” but still says it has a “persistent household identifier” for its customers.

Editor’s Note: Our work on privacy, security, AI, price transparency, and financial technology issues is made possible by the vision and support of the Ford Foundation, Omidyar Network, Craig Newmark Philanthropies, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.