How Driver Monitoring Systems Can Protect Drivers and Their Privacy

These systems could eventually stop drunk drivers, but privacy experts say the feature should be introduced very carefully

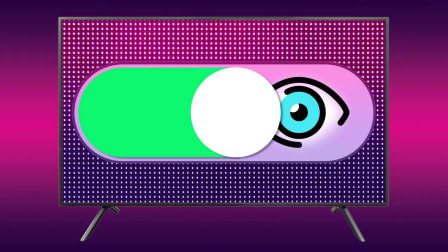

Driver monitoring—using cameras and sensors to determine if a driver is paying attention—is becoming an increasing part of modern vehicle safety. But privacy advocates warn that there’s a big difference between cars that can tell if a driver is looking at the road and cars that collect and share information with marketers, insurance companies, or even law enforcement, all without giving the driver control over how the data is collected and used.

Manufacturers of most driver monitoring systems available today claim that they don’t capture or share identifiable information about a vehicle’s occupants. For example, BMW, Ford, General Motors, and Subaru told CR that none of their vehicles equipped with driver monitoring features transmit data or video from the system beyond the vehicle itself.

But the landscape is changing rapidly. A new federal law could lead to a requirement that automakers develop driver attention monitoring as a way to reduce driver distraction. A part of that law would eventually require automakers to equip all new vehicles with a system that could restrict impaired people from driving, technology that could save lives but also require careful attention to privacy concerns. Tesla can already capture video from inside a car’s cabin and—if the driver chooses—send that footage directly to the company, which it could conceivably use to determine fault in a crash. In Europe and Japan, automakers are already implementing systems that can detect driver impairment.

Privacy by Design

Experts tell CR that engineers developing these systems should take privacy into account throughout the process. This follows a concept developed by privacy researchers known as “privacy by design.”

For example, the infrared cameras built into the first versions of GM’s Super Cruise weren’t designed to have any sort of facial recognition or video capability, says Charles Green, a retired GM engineer who helped create Super Cruise and is now a research scientist working with the MIT AgeLab’s Advanced Vehicle Technology Consortium. “The only thing this system is trying to do is to try to figure out if you’re looking at the road,” he says.

Serious Consequences

Provisions of the recently passed infrastructure bill promote driver attention monitoring, but they also go a step further by calling on automakers to build new systems that can restrict an impaired person from driving. These systems, which might be based at least in part on driver monitoring technology, could save thousands of lives each year, says William Wallace, manager of safety policy at CR.

“These systems wouldn’t be like the blow-in-a-tube devices that offenders have to use,” he says. “Instead, what the law requires is technology that can passively and accurately detect impairment. It would exist in the background, and normally you’d forget it’s even there. But if there’s a drunk or drug-impaired driver, it would effectively stop them from operating the vehicle.” Research from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) shows that an alcohol-detection system that stops people from drinking and driving could save more than 9,000 lives per year, preventing about one-quarter of all the deaths that happen on U.S. roads.

Driver monitoring is never foolproof. But when the driver attention monitoring systems in today’s vehicles make a mistake, the consequences are relatively mild. Super Cruise, for example, might sound a warning or briefly take away automatic steering and acceleration features if it has trouble detecting where a driver is looking. But the stakes are higher if a system is trying to detect driver impairment, says Nandita Sampath, a policy analyst at CR who focuses on algorithmic bias and accountability issues. For example, if a car is stopped on the side of the road or left in a parking lot, law enforcement could stop to investigate. “A false decision could lead to a car getting pulled over or, at worst, an arrest or other loss of liberties,” she says, adding that serious consequences based on a driver monitoring system should have contestability built in. That means drivers should have the ability to push back against false or wrong decisions.

Sampath warns that regulators need to be certain that these monitoring systems will be able to accurately detect what they’re supposed to—whether it’s fatigue, impairment, or distraction—and do it consistently for a wide variety of people, taking into account variations in skin color, clothing, and accessory types, such as sunglasses, hats, and face masks.

Automakers also need to clearly tell drivers what personal data a vehicle is collecting, Colbert says, so drivers can ask themselves whether the benefit is worth it. “What type of implication is this going to have on my insurance, on my work, on my driving record, with law enforcement?” she asks.

More Proof Is Needed

Privacy experts say that policymakers need to anticipate how the personal data that vehicles collect could be used or misused, especially if these systems are being used to penalize drivers.

Some states and municipalities have already banned most government uses of facial recognition, although it often doesn’t apply to private companies, such as automakers. In 2008 Illinois required that anyone in possession of private biometric data get consent for its collection and develop policies about its use and destruction. A pending court case claims that this law applies to driver monitoring systems. Such regulations could have an impact on the implementation of driver monitoring systems. In addition, drivers may balk at using systems that they worry won’t show respect for their privacy rights, Colbert says. “What if people try to do things to block those safety systems?” she asks, such as covering up a camera.

In CR’s tests, the current crop of driver monitoring systems can reliably detect and react to distraction with different drivers at night and when using a mask or sunglasses. But more work is necessary to learn if they’re reliable enough for other uses, says Jake Fisher, senior director of CR’s Auto Test Center.

“While they aren’t perfect, these systems are effective and should be used to help the driver stay engaged when using automated steering and speed control,” Fisher says. “But more research is needed to determine if a monitoring system can reliably detect a drunk driver.”