How Social Platforms Are Scrambling to Slow the Spread of Election Falsehoods

Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and other tech platforms are labeling some posts and deleting others

Between Sept. 30 and Oct. 8, an advertisement on Facebook promoted false stories about the election, including one about “hundreds of piles" of Republican ballots being dumped as part of “a massive underground mail-in ballot fraud coordinated by Democrats.”

Facebook displayed the advertisement 30,000 to 40,000 times, mostly to people over 65, at a total cost of less than $200. Then, after being notified about the falsehoods by the Election Integrity Partnership (EIP), a nonpartisan coalition of researchers, Facebook removed the ad.

But the untrue stories remained on the platform.

Like many ads on Facebook, this one appeared in a regular post that a person managing a Facebook page paid to promote. The page belongs to a shadowy operation called Plain Truth Now that is run out of Nigeria, according to the EIP. It seems to be coordinating its messages with a related website to spread false claims about the election and social issues.

Facebook stopped promoting the post as an ad but didn’t take it down. The same post appears on the Plain Truth Now page and on other pages where it's been reposted, including one Facebook Group with tens of thousands of members.

That incident shows the surprising ways the rules can play out as social media companies try to slow the spread of election-related falsehoods or misinformation. Blocking misleading ads is just one of several tactics Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and other companies are using. If you use these sites regularly, you may find the platforms making it harder to share certain posts, adding warning labels to many others, and employing an evolving group of other tactics.

Links and Labels on False Claims

One tactic you'll probably encounter are the labels and links social media companies are adding to some posts, including those they identify as misleading.

Facebook says it added such labels to 150 million pieces of content between March and September of this year. Twitter and YouTube use similar labels.

fb fb

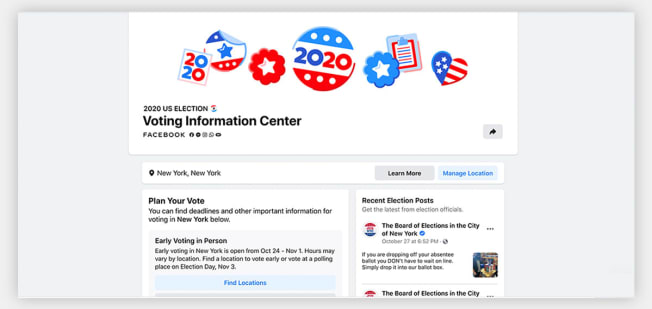

Facebook, Snapchat, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube are maintaining voting-information hubs on their platforms. And the companies are placing links to information on or near a variety of posts that discuss the election. The links appear on many posts, not just those that may contain misleading information.

Some people who study misinformation and content moderation say that labeling dubious—but not harmful—content and providing links to better information can be better than deleting a post. “Taking down misinformation doesn't necessarily mean people will be directed to true information,” says Evelyn Douek, a lecturer at Harvard Law School who studies social media. “I think we need to get out of the ‘take down, leave up’ false dichotomy. There are so many more things that platforms can do."

On the other hand, critics of the technique say there’s some evidence that adding a label may draw more attention to a misleading post that might have faded into the background otherwise.

twitter twitter

But it's hard to know just how well these techniques work, according to Kathy Qian, co-founder of Code for Democracy, a nonprofit organization that uses public data to study misinformation and dark money in politics. "There isn't really a systematic way for someone who isn't a partner with these companies to get access to the right data to make any kind of judgment about how effective these efforts are," Qian says. "You basically have to take the platforms at their word."

People can also disagree sharply over what kinds of posts should be suppressed. Making those calls can sometimes be more difficult than putting the techniques into action.

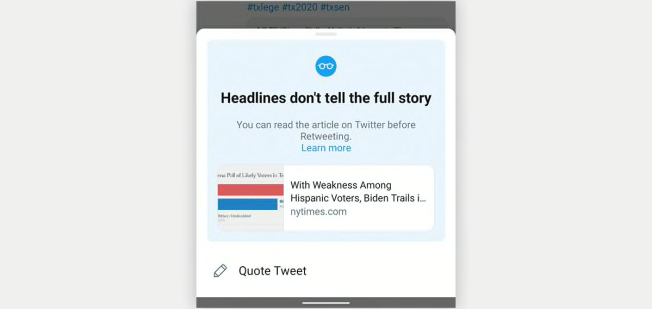

Just look at what happened on Oct. 14, when The New York Post used social media to post links to an article saying that documents allegedly taken from a laptop by a computer shop implicated Joe Biden in a corruption scandal.

Twitter displayed a warning that said the “link may be unsafe” if users tried to retweet a post that linked to the article, and stopped users from tweeting fresh links to it. The company said it was enforcing policies against tweets based on hacked or stolen material, and against images of personal information such as email addresses. Facebook temporarily made the article less likely to appear in a user's feed while it said it was determining its accuracy.

But the companies were both accused by many people of suppressing a legitimate news story. This week Twitter's CEO, Jack Dorsey, was grilled on the issue at a Senate hearing.

Banning Political Ads

You'll probably see fewer political ads on social media right now, especially ones that refer to breaking news.

Facebook barred advertisers from purchasing new political ads starting a week before the election, and says the ban will continue for an unspecified length of time after.

Google says it will place a moratorium on ads on its platforms related to the election while votes are being counted. Political ads are allowed on Snapchat, but a spokesperson told CR that they must go through a human review process before posting and that they must be factual.

In addition, all political ads are banned on Twitter, Tik-Tok, and Pinterest.

Experts on social media and misinformation say that ads are just a small part of how conspiracy theories, deliberately misleading information, and lies about the voting process spread on social media platforms. During the 2016 election, Facebook says, approximately 126 million people—about 1 in 3 Americans—may have been exposed to about 80,000 pieces of content sponsored by Russian state actors and their proxies, and spread by regular accounts, not ads.

But that doesn't mean these rules won't help, says Harvard’s Douek. “Advertising policies are the lowest hanging fruit," she says. "I'll take it."

Blocking QAnon and Similar Content

The most extreme thing social media companies do is to delete content or cancel entire user accounts.

The clearest example of this is how Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other platforms have been trying to tamp down QAnon messages. The wide-ranging conspiracy theory alleges that the President Donald Trump is waging a secret war against prominent Democrats and deep-state actors who worship Satan and run an international child sex-trafficking ring.

Reddit banned a number of QAnon-related groups in 2018 and expanded its takedowns this summer in response to harassment and incitements to violence among Q followers. Other platforms have recently started deleting accounts linked to QAnaon as well as groups devoted to the Boogaloo, a far-right, antigovernment movement. Facebook, reversing a longstanding policy, said it would start removing Holocaust-denial content.

Some critics of these companies say they should have acted more forcefully earlier, before QAnon, in particular, exploded in popularity on the platforms.

Questions about where social media companies should draw the lines around free speech are complicated, says Brendan Nyhan, a political science professor at Dartmouth College who studies media and misinformation.

But, he says, they should explain their decisions better. "There needs to be more accountability and more discretion about their decisions, and the effects those decisions have," Nyhan says.